Beijing’s lost water transportation system

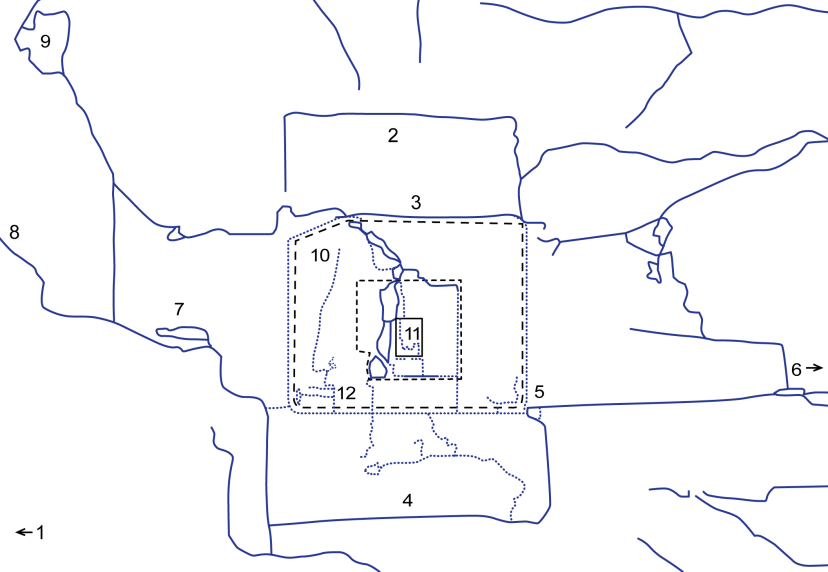

The major river in the Beijing area, the Yongding River (1 off map), was discovered to be too fast and prone to flooding to afford urban habitation, so the city was built some ten kilometers northeast of the river when founded in the late Liao/Jin Dynasty (mid-12th c.), and thereafter shifted further northeast in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). The first moat formed a square around the city’s walls. Today, the northern section of the moat has been restored and beautified and renamed the Xiaoyue Moat (2). Its former name, Beitucheng (north wall), is now given to a stop on subway Line 10, which runs alongside the moat.

_____ existing canals and moats

……… former canals and moats

_ _ _ _ former Inner City and Imperial City walls

In the early Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the city’s north and south walls were shifted southward about three kilometers and one kilometer respectively, which required the rebuilding of the two walls, while the east and west walls and moats were retained. The pre-existing canal connecting Jishui Lake to the Ba River in the east became the new moat, Beihuchenghe (north moat), lying just outside the new north city wall; this moat has been restored and beautified (3).

The Ming Dynasty city wall lasted until the 1950s, when tragically Mao Zedong had it razed, and most of the moats covered up or allowed to languish (the idiots somehow managed not to have Xi’an’s city wall torn down). In its place was eventually built the subway “Loop” Line 2, whose route exactly follows the former city wall (outer dashed line).

Beijing city wall, late Qing Dynasty (Find the Old Beijing, China Nationality Art Photograph Publishing House, 2005)

Remnant of the Beijing city wall at Dongbianmen (5 on map). The Corner Tower, formerly known as the Fox Tower, is featured in Paul French’s Midnight in Peking.

In the fifteenth century the Ming rulers began to build a second city wall to encircle the first, but only the southern section was finished before funds ran out. To distinguish this section of the city from the one inside the original wall, it was designated the Outer or Chinese City as opposed to the Inner or Tartar City (“Tartar” referring to the Mongols who had controlled the city during the Yuan Dynasty), the two cities divided by the Tartar City Wall (i.e. the south Inner City wall). Today the North Second Ring Road expressway follows the former Inner City wall on its north, east and west flanks, and the South Second Ring Road follows the former Outer City wall on its south, east and west flanks.

The moat surrounding the Outer City wall has been restored and lies just inside South Second Ring road (4). It feeds into the Tonghui Canal at Dongbianmen to the east (5), which in turn feeds into the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal in the eastern suburb of Tongzhou (6 off map). To the west, the moat is connected to Yuyuan Lake (7) and beyond that the Yongding Diversion Canal (8) that links up with the Yongding River at Sanjiadian Bridge (off map). This forms a continuous east-west aquatic route across the city. At some 65 kilometers (40 miles) in length, it must be one of the longest intra-city canals of any metropolis in the world. It is no longer used for transport, apart from the transport of water itself for the purposes of flood control and the intake of water into the city from the Miyun Reservoir to the city’s north.

The Yuyuan Lake formerly served as an excursion retreat for the Imperial family and was connected by canal to the Inner City to the east. Today, a pleasure boat takes you from this lake to Kunming Lake and the Summer Palace to the north (9) via the Beijing-Miyun Diversion Canal. An alternative pleasure tour starts from Nanchang Canal behind the Beijing Zoo and passes through Purple Bamboo Park before joining the same Beijing-Miyun Diversion Canal. The latter route in reverse originally drew waters from Yuquan Hill to the west and Baifu Spring to the north of Kunming Lake down to Jishui Lake (10) at the northwest Inner City wall, for supplying water to the Inner City. The tiny West Lake just to the east of the Jishuitan subway stop on Line 2 is all that remains of the once large Jishui Lake. It’s the westernmost of a connected string of six lakes, Xihai, Houhai, Qianhai, Beihai, Zhonghai, and Nanhai. The latter three lakes were formerly enclosed by the Imperial City (inner dashed line) and fed into the Forbidden City.

Like the Inner and Outer Cities, the Imperial and Forbidden Cities had their own moats. The Forbidden City moat remains and is now named the Tongzi Moat (11), while the Imperial City moat has disappeared (except for a restored half-kilometer stretch on the southern end). In fact the Imperial City once had its own system of canals serving as conduits for different types of goods (mostly grains and luxuries) received from the east and south inner city moats and in turn the Tonghui Canal (5), for transport to and from the Grand Canal to the east (6), thus forming the original east-west transport artery.

Apart from the Tonghui Canal and a few waterways that have been diverted underground, this former canal system has largely disappeared (former canals and moats of the Inner and Outer City are indicated by dotted lines; I lack data for the outer-lying city). Transportation of goods and people is now accomplished by road, rail and air. Beijing’s canals and moats still serve the important function of flood control but beyond that are decorative at best and eyesores at worst. (We must not be under the illusion, however, that the moats and canals of the past, mostly stinking sewage traps with dirt embankments, were a pleasant sight; the concept of urban beautification is quite modern.)

The map starkly reveals this. Note how many canals start and stop without joining up to nearby canals. In some cases, they were once connected until blocked and filled in to make way for roads and development. In other cases, new ones were built for flood control or farmland irrigation (until the past two or three decades, much of Beijing beyond the Third Ring Road was rural).

This fragmentation of Beijing’s water system is hugely significant, to my mind. I emphasize my personal reaction here since during the two decades Beijing has been my home, I have yet to encounter a single person who has had anything to say for better or worse about its vast but practically defunct water system. The ghostly network has disappeared into the woodwork to such a degree as to render it invisible, not amenable to conscious awareness in the city’s psyche, despite being right out in the open.

In the aftermath of the 2012 flooding, few news reports mentioned the vital role of the canal system in containing the torrents of rain; attention focused exclusively on the city’s aging drainage system. One exception was an article in The Economist (“Under water and under fire,” July 28, 2012) correctly noting that much of the blame falls on the decision in the 1950s to fill in many of the canals along with the moats at the time the city wall was torn down. Even as the canals come to life in sucking up vast quantities of surging water, their important work is unseen while in plain view, below the threshold of consciousness. But only up to a point. All that is needed is another rainstorm with slightly heavier precipitation to cause the canals’ water to loom up and wash over the city. It may finally take a major flood to force the canals back into public awareness and respect.

You can’t get very far in Beijing without crossing a waterway. Yet you’ll receive a blank stare if you ask a local you’re with the name of the canal behind you. He or she will have no recollection of having seen, only seconds before, any canal; you need to drag the person back with you to the canal to prove that it exists. It’s also why I had to create my own map of Beijing’s water system. No relevant maps or books can be found in any of the city’s major bookstores. Even the city’s historical museum, the Beijing Planning Exhibition Hall, had no information; I failed to get any of the museum’s staff to grasp the import of my question (this was not due to any problems with the language). I didn’t have the patience to investigate the National Library.

Coming myself from a city with a large waterfront, Chicago, I have always been interested in the intimate, sensuous relationship of cities and water. Most cities straddle water, whether a river, a lake, or the sea. Perhaps because Beijing lacks an imposing seafront or centerpiece of a river but has only canals, and not especially attractive ones, they are regarded as trivial when noticed at all. But if the total distance and volume of the city’s canals were added up, if they were imagined as forming a single interconnected body of water, which in fact any canal system is, it would be substantial. Like Beijing itself, a city too big to take in at a glance, with no single center or skyline but many centers scattered around, its water system is not visible in its unity but only in isolated patches. Still, if imagination is required to conceive the whole, imagination is also capable of transforming it into something even more conspicuous and magnificent, an organic, living thing.

An imagined future water transportation system

With half a million people moving into Beijing every year to live and work, the city’s population is now officially pegged at 25 million (though actually much higher). Its streets are gridlocked with thousands of newly purchased cars added daily and choking with air pollution, while an expanding subway system is trying to absorb the flood of people. But instead of picking up the slack, it just gets more crowded and harder to use, as each new subway line that opens up only enables greater numbers of people to use it. But there is a potentially magnificent public transportation system begging to be developed: transportation by boat along the city’s moats and canals.

I mentioned above that pleasure boats already carry sightseers along two overlapping routes to the Summer Palace, totaling some 20 kilometers of territory. If all of Beijing’s waterways were enabled for public transportation, the total distance in kilometers would rival the territory covered by the existing subway system and would carry commuters to most corners of the city and suburbs. I’d hazard a guess that the navigable waterways of greater Beijing (within the Sixth Ring Road) add up to several hundred kilometers. The city’s navigable length would be even greater if previous canal routes were rebuilt and existing ones extended to connect to other canals in a comprehensive network. This network would moreover have the added benefit of greatly enhancing the margin of safety during flooding, with water given more space to move and disperse. The cost of this could be steep, but not anywhere near as astronomical as the per-kilometer cost of building a subway line. And the bulk of the labor has been completed, as most of the potential waterways already exist. Together they take up a huge amount of land. It seems tragic that they sit virtually unused.

The biggest obstacle is water itself, specifically the severe water shortage in the north of China. While water transfer projects from the Yangtze River to northern China are in progress, water remains at a premium. Huge amounts would be needed to enable a properly functioning aquatic transportation system. Yet this need not preclude the developing of such a system, given the need for it. There is currently enough water to go around for vanity projects such as the obscenely water-hungry golf courses springing up all over Beijing in recent years.

Other serious but not insurmountable technical obstacles: 1) Removal of the numerous sluices, weirs and gates (many unused) controlling the flow and rationing of water that presently segment the canals, in order to allow for the passage of boats, along with the raising of low bridges and the widening of narrow passages to allow for bigger boats to make passenger traffic feasible for thousands of commuters. 2) Preserving adequate means of flood control, e.g., by maintaining dry canals to absorb excess water during heavy rainfall. Additionally, other dry canals could be paved and converted into monorail-cum-bicycle routes. If we really wanted to get creative, naked bike riding could be permitted along these routes to attract more people to use them (not as farfetched as it sounds: www.worldnakedbikeride.org).

The water transportation system could be built incrementally, canal by canal, starting with the city’s greatest priority, the Tonghui Canal, to alleviate the huge stress on public transportation between the central business district and the massive suburb of Tongzhou, a substantial city in its own right. Boats could be designed for different kinds of canals, with larger canals handling more types of boats—larger craft for local traffic, smaller craft for express service and fewer stops, etc. Boat stops stationed a kilometer apart could be easily accessible by steps from street level; and the canal routes beautified with attractive greenery and landscaping. Boat commuting would be fun and although more crowded as it became more popular, more relaxing than the crush of the subway or the traffic and exhaust of the streets. City life along the canals would flourish, with the mushrooming of local businesses suited to the mostly residential communities, such as teahouses and—virtually nonexistent in China today—neighborhood public libraries.

I try to re-imagine the canal, or river, that once ran from the now shrunken Jishui Lake (10) south to the south wall moat (roughly from today’s Xinjiekou to Xuanwumen). If this waterway still existed, you would find at one bend a storied old teahouse named the Sanwei Shuwu, on Tonglinge Road just south of Fuxingmen Inner Street (12). Opened in the 1980s by a university professor couple who had spent two decades in prison after accused of being Anti-Rightists, it was a hangout for democracy intellectuals until the fun was again abruptly ended in June 1989. The teahouse and its first-floor bookshop survived. I often visited it in the early ’90s, when there were few other tea or coffeehouses in the city. The airy interior with its hardwood furniture, birdcages and skylights was an elegant venue for Chinese classical (and occasional jazz) concerts and book talks as well as afternoon tea. Today amazingly, sandwiched between massive office buildings, the Sanwei Teahouse is still open, though few people seem to know about it.

The Sanwei owners’ daughter, incidentally, got in trouble in 1989 for running her own democracy-literature café and was caught after going into hiding. Upon her release from prison, Shasha ended up in of all places the Friendship Hotel, which up through the 1980s was one of the few foreigner-approved accommodations in the city. After moving in with her American boyfriend she was picked up by the police, only to be returned after a friendly senior officer at the station recognized her. She thus became the first Chinese female allowed to cohabit at the famed hotel with a foreign male—who happened to be my neighbor. Since he was fluent in Chinese, she sought someone to tutor her in English. I discovered how liberated Shasha was during our first English session. She curled up next to me on the floor and, her shirt dipping open and naked breasts delightfully in view, described in halting English her twin research projects on Tibetan burial practices and Chinese who become transsexuals.

Then they moved to a beautifully restored ancient hutong flat in the Deshengmen area, where they entertained Shasha’s journalist friends in lavish parties. Then we were together. Then she married him and they left for the US. And then she dumped him, and that’s the last I heard of her.

Just south of the Sanwei teahouse was a store selling collectible Yixing (purple sand) teapots. Browsing in the store one day, I noticed a teapot selling for 1,000 Yuan that was identical to one I had bought in Tianjin for 40 Yuan. Pointlessly, I confronted the clerk about the fraud, and even returned to the shop with my teapot to prove it. Across the street was a narrow lane, where the canal would have zigzagged west before resuming its northern course. On one side was an old-fashioned WC without partitions inside, compelling shy users to hold up newspapers for privacy. On the other, the marvelous Tiantian dumpling restaurant, where I had my first taste of venison jiaozi. The lane still exists today, more like a service road now behind one of the big office buildings, the old structures gone and the history erased.

If Beijing reclaimed its water system, the city would take on a completely different look and feel. A major shift in perspective would occur, as a seemingly whole new city unfolded out of nowhere, lush canals that people hardly knew existed popping up everywhere like something out of Harry Potter, the coordinates of the bleak city reset against instead of along the grid pattern, with crowds walking in different directions along undiscovered streets to get to and from their usual destinations by something unheard of: boat. With this transformation, Beijing might become known as a great city of canals. More tourists would be drawn to the city for this reason alone than all the usual tourist sites combined.

The poverty of the institutional imagination

Canals that begin out of nowhere and terminate suddenly only a short distance from other canals, disembodied and shorn of their history, whose water is prevented by sluices and gates from flowing freely, leaving some sections full and others empty and dilapidated: a profoundly metaphorical phenomenon in the Chinese context. It can be likened to the flow of information in China, which is also a consequence of power’s hermetic tendency. Societies have traditionally hoarded information and prevented its flow. Until the last couple centuries (the American and French revolutions were turning points) information was universally treated as a kind of currency the powerful could enrich themselves with and dole out to the rabble in crumbs in return for good behavior (i.e. supplying the powerful with real currency in the form of taxes). That is why literacy—the information canal—is a relatively modern prerogative; it undermines and threatens power.

The Chinese library is a telling example of this in microcosm. The National Library in Beijing, the biggest in the country, has recently expanded into a massive new building and its services improved. One has to give the government credit for recognizing that a library for public use is something worth investing in. The older section of the library was modeled on the factory: you waited up to an hour for a book to be delivered literally by a conveyor belt from unseen stacks and then return it within a short space of time, without leaving the library (higher-ranked people such as professors could take books home). You had to surrender your ID even to read magazines in the periodicals reading room, while certain journals were off limits to all but the professionally credentialed or those with connections. There was no way to request or access books already borrowed by elite users of the library, who could hold onto them indefinitely.

It’s not that there is some government conspiracy preventing people from reading or restricting the nature and amount of resources available to them. It’s more haphazard than that. Just as information is itself treated as something cheap and shoddy, not worthy of much attention, local public libraries are not considered worthy of funding, despite the relatively modest financial outlay they would require. Neighborhood libraries for use by the general public are few and far between; only major cities have more than a single central library. Beijing has more than most, with twelve public libraries, averaging some 1.6 million potential users for each (bookstores don’t fare much better: try to find one in any large shopping center in Chinese cities). And with no tradition of community libraries, ordinary Chinese would need to be educated about their value—the value of free and universal access to knowledge—before the idea could take off. Average Beijingers likewise need to be enlightened about their universal right to public space, otherwise known as the public commons, including the resource of the canals in their midst.

The idea that there is not enough information to go around to afford free access can be described as the “scarcity mindset.” It applies to people as well, whenever they merely try to get through the day, to struggle and survive, despite having enough of everything materially speaking, when instead they could devote the same energies to enjoying life and being more creatively productive. Beijing’s fragmentary canal system too, with a mere handful of canals and moats beautified while so many others remain dysfunctional or decrepit, mimics people’s stunted life trajectories, unable and unconscious of any need to self-actualize, to join up with others and form intentional communities, the way the canals could potentially be extended and join up with other canals to complete and synergize a true water transportation network.

For more information on Beijing’s moats and canals:

Virginia Stibbs Anami, Encounters with ancient Beijing: Its legacy in trees, stone and water

Irving Hultengren, Beijing’s forgotten waterways

D. J. Clark, Beijing waterways

* * *

Like this post? Buy the book (see contents):

At the Teahouse Café – Essays from the Middle Kingdom

Related posts:

How to have fun in China’s disposable cities

The Chinese art of noise

Categories: China

Beijing only does enough for what is needed at the present time—-the canals were made beautiful for the throngs of tourists of the 2008 Olympics—-the water was even dyed very green in some locations. And their bizarre idea of reverting waters from southern rivers to the north is about as stupid as planting trees in the northern city areas to stop sand storms which invades Beijing at times—–the sands from the Gobi are usually cloud level when swooping into Beijing. Most or all of Chinas water comes from Tibetan glaciers that are quickly melting away and thus the reason why the Yellow River and others are drying up. If the government seriously did build a canal system reverting even more water from these drying up rivers it would add to the mounting catastrophe that is the massive water shortages in China. Only about 40% of all surface water in China is “ok” for drinking purposes—with the other 60% not even up to standards for ANY other purpose—meaning it is too polluted with chemicals and other substances. As for so-called bottled water it too can be and IS very questionable as to its origin with even large bottling companies like Nestle being caught selling tap water in recent years. When visiting China—drinking beer is one of the safest things to drink……”foreign” beers.

When I first came to Beijing in 2004 I had a sense of excitement coming to the “capital of China” with its 3000 year old history. At first I was much more interested in catching a feeling for the grandeur of the imperial past than paying attention to what felt like a third world modern city, judging by the neighborhood I landed in. The waterways played an important part in my imagination of the past. I used to look at the canals and imagine the flotillas of the royal elite and their entourages and all the pomp and pageantry involved in going from place to place. I still have a strong desire to get a canoe and just paddle around and while away a lazy day as the frantic pace of the city life zooms by without even knowing or caring I`m there.

Do it! You’ll get in the news, though, and probably arrested. I’m sure they have some law against individuals using the canals without authorization.

I used to see peasants and most likely locals swimming in them in the summertime by JiShuiTan subway line….I don’t think the government cares a lick about who uses them or how just as long as it doesn’t cause any “issues”….

I have explored the canals a bit around guomao, and it’s interesting. There’s a really rickety, dusty rotting old train bridge about 1km east along the canal there that’s out of another world.

Have you written about public space in China in general? If you look at the land use east of guomao bridge, on the south side for example – the road is really wide, with busses always passing by. Then there’s a little narrow bus-stop / waiting area that’s packed. Then there’s a 10m wide sort of garden area – thousands of exactly the same species of space-filling plants, just taking up space, without any place to sit or actually go inside. It’s so unimaginative – just the result of some directive that a certain amount of “green space” be needed. But since they’re terrified of creating any space where a group of people can gather together, they make the green space dense and useless.

The same with park design – Chaoyang park empitomizes so many things that I don’t like about China. Fields choked of identical plants, almost no fields/public space that isn’t commercial (but acres of water that you can’t swim in, huge monoculture forests), constantly shrinking as bites are taken out of it to build malls, car dealerships, parking lots… speaker systems constantly blaring announcements or just being broken and buzzing… employees who speed around carelessly on walking-only paths, how they forbid people from bringing in bikes…

And parks are the same all over the country – I’m sure they’re all designed based on some central chinese guide on how to build parks, that every civil engineer studies.

Tiantan park just shows how much better things can be done.

It is in point of fact a nice and useful piece of information.

I am happy that you shared this helpful information with us.

Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Reblogged this on iLook China.

Very interesting article and comments. I am surprised at Beijing’s lack of libraries and the restrictions of use. Is this true of Shanghai and other cities? When I speak about reading many books, it has always seemed incongruent with many scholarly Chinese I know. While they are brilliant in math and science, they know little about literature. Novels? Fiction vs. non-fiction?? Now I understand their confusion.

Some of my favorite books are by Chinese, including Amy Tang, Anchee Minh, and the author of “Red Sorghum”, I think Ma.

Reblogged this on Vanessa's Blogueria.

To be fair, public libraries are next to non-existent in Italy, the country of my birth. The truth is that only in English-speaking and Northern European countries do you find public libraries worth the name. It’s already something that in Beijing they exist at all.

Thanks for the useful piece of information.