THE CLASSROOM EXPERIENCE

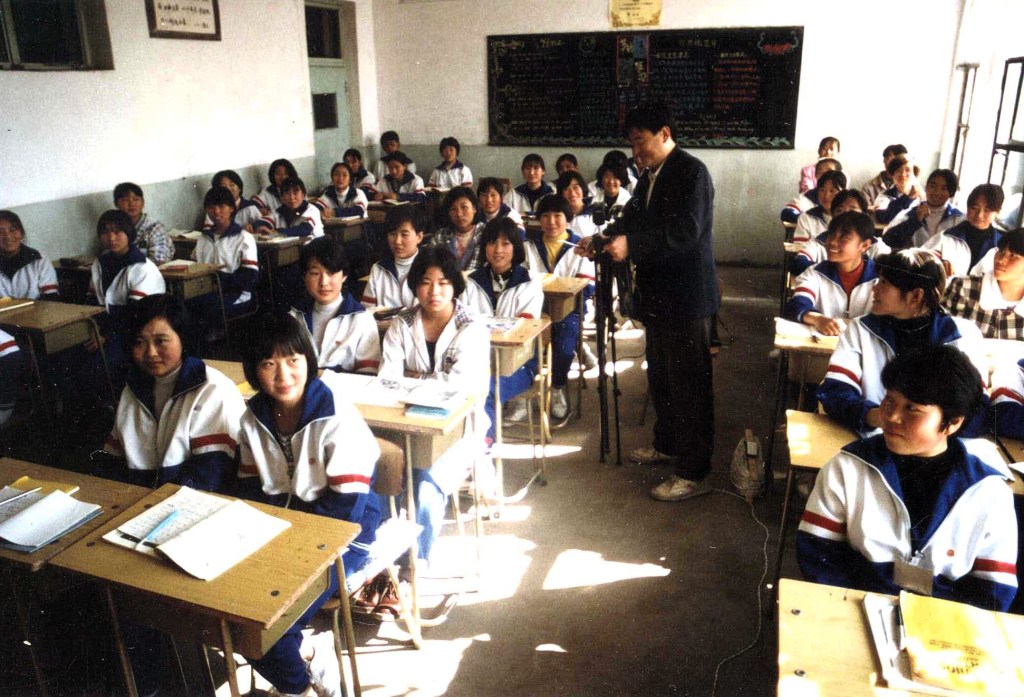

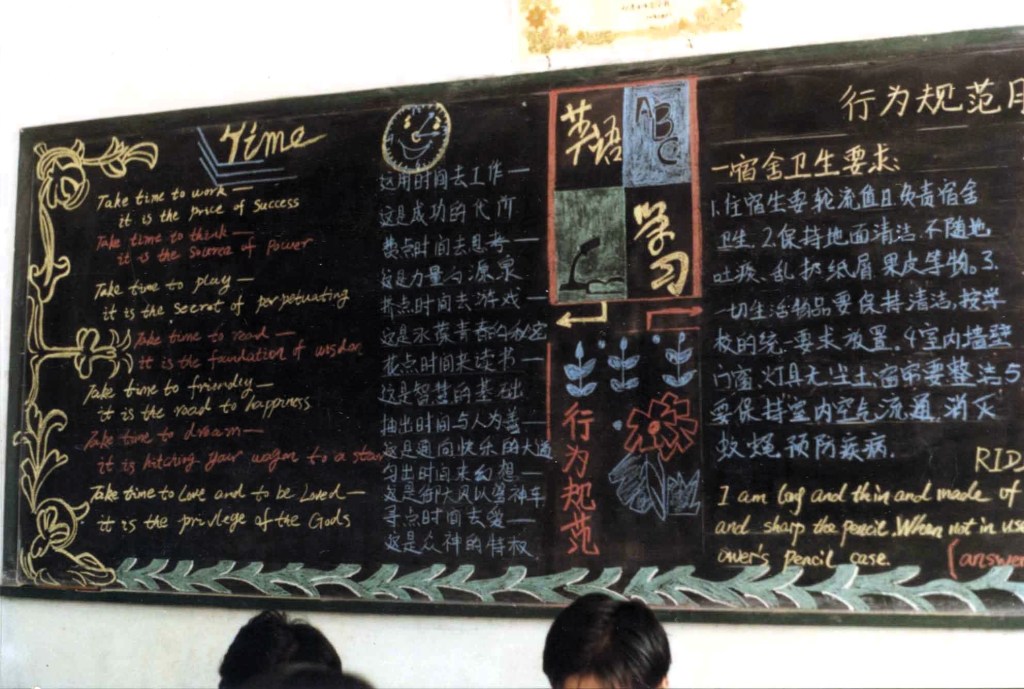

You can begin to understand the Chinese educational system just from viewing a few photos of classrooms. And what you’ll discover is that it differs not all that much from the educational systems of many other countries. The photos at right show a high school I visited in Beijing in 1996, invited by a former student at the normal (i.e. teacher-training) college where I was then teaching. She had by then graduated and become a teacher herself, pictured at the lectern. It’s a typical classroom, holding about fifty students, seated at paired desks arranged six across and eight deep. The seating is generally fixed by the teacher. Some teachers award high-achieving students the choice of their own seats and seating partners; other teachers put taller students in back for better visibility (this female-dominant classroom has only two boys, sitting in the back corners). For comparison’s sake, see the photo below of a Japanese high school I taught at in 1990, also with fifty students. The only telltale difference is the gendered uniforms in Japan (sailor suits for girls, military jackets for boys), versus the unisex tracksuits in China. The classroom layouts are otherwise the same.

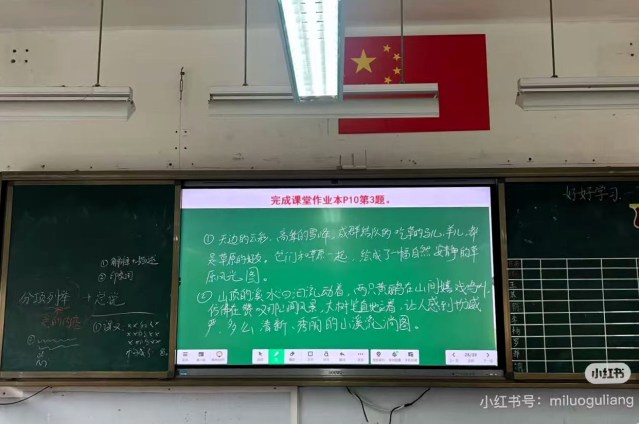

Apart from advances in technology, little has changed over the three decades since I visited that Chinese classroom. Computerized touch-sensitive LED screens have now pushed aside the old blackboard or are used in conjunction with blackboards or whiteboards. Eye-friendly ceiling lighting that filters out blue light has replaced fluorescent lighting. Classrooms are more spacious and increasingly shifting from six-across/eight-deep to eight-across/six-deep seating arrangements, bringing the students at rear closer to the teacher and the screen. The photo below (grabbed from the web) shows a typical LED screen, with the teacher’s notes on good prose style. The photo below that was taken by a university student of mine of her former high-school classroom, from which she graduated in 2024. Notice at far right the poster their teacher chose to put up on the wall, featuring a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra on the “three metamorphoses of the spirit,” symbolized by the camel (self-discipline), the lion (independence and the challenging of authority), and the child (spiritual liberation and creativity).

Compared to public high school education in North America and Europe, the Chinese high school experience is far more rigorous and would scarcely seem believable or bearable to those unaccustomed to it. Let’s briefly go over the basics for the three years of senior high school (while noting that junior high school is similar). Most Chinese high schools are what we would call boarding schools, with dormitories for the students. This is logical for those from the countryside who’ve been accepted into a higher-ranked school rather than a lower-ranked one closer to home. But even where the students’ homes are in the same city they are typically required to live at school, for the first year at least, and may apply to be day students during their second and third years. Even day students must remain at school for evening self-study before being allowed to go home, though these strictures can vary and some schools are laxer, laying this responsibility on the students’ parents.

Since they live at school, the school day begins not at the start of classes but at waking time and ends when the students are released from self-study in their classrooms in the evening. Typically, this means a sixteen-hour day, either 5:30 AM-9:30 PM or 6:30 AM-10:30 PM, seven days a week. They may arise an hour later on Saturdays and Sundays, and Sundays have only morning classes (a few luckier schools give students one and a half or two days off on the weekend). In other words, the students have scarcely any free time in their lives. This is intentional and I’ll return to this point below. It also explains much about students’ attitudes and behavior when they arrive at university.

THE HIGH SCHOOL CURRICULUM

During their first year of senior high, all students take the same compulsory subjects—Chinese, English, mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, politics, history, and geography; some schools have an additional course in information technology. In their second year they are tracked into Science or Humanities. They can then select relevant elective courses from among the first-year subjects to deepen their knowledge, while Chinese, English, and mathematics remain compulsory. Teachers have considerable leeway in deciding how much time to devote to scripted content and how much to digress. However, from the second semester of their second year, there is a shift from general course content to preparation for the nation-wide, four-day university entrance examination known as the gaokao. The same subjects are now “taught to the exam,” that is, with more emphasis on anticipating exam questions. In their final year, schools that allowed them to carve out a bit of extra time for club activities or hobbies such as badminton, calligraphy, or piano now strongly discourage or forbid the students from devoting their waking hours to anything but gaokao preparation. There is so much focus on the gaokao that many high schools will sacrifice physical education, except perhaps for making the students run a few laps around the track in the morning. For an in-depth look at how one subject, history, is taught in Chinese high schools, see my Questioning China’s “5,000 years” master trope.

Likewise, there is much less student-centered group or pair work in Chinese than in Western classrooms, as it’s considered less efficient than dispensing knowledge directly by the teacher. More enlightened teachers, particularly in English classes where speaking skills obviously can’t be developed without active participation, do encourage the students to speak up to a limited extent. Students are even allowed or invited to assert their own opinions and point out the teacher’s errors. The younger generation of teachers seems to more open to two-way interaction in the classroom. Most of the students I talked to had mostly favorable impressions of their teachers, who tried their best to make their classes lively and memorable under the constraining pressures of exam-based education.

PRESSURE-COOKER EDUCATION

After talking to numerous students about their school experience, I came away with two interesting and somewhat contradictory insights. On the one hand, beloved teachers aside, they were unanimous in their conviction that high school was tedious and exhausting. A common reaction was they had no memory of what they had learned—even just after they had graduated!—the entirety of their knowledge having emptied out of their brains onto the gaokao examination paper and dispensed with for good. Their only happy recollection was time spent with their friends. On the other hand, many were nonetheless grateful for the ordeal, precisely because it was so grueling. They were quite cognizant that the severe process they had been put through honed the intelligence, formed character, and to a great extent better prepared them for study abroad than students from less rigorous backgrounds. During my years teaching college composition in the U.S., I similarly recall the striking difference between freshmen students and their slightly older compatriots who had spent a couple years in the army before entering university, who were so much more mature, calm, and focused.

The Chinese high school system is designed as a merciless but efficient filtering device. Only those who survive it have the right stuff to advance up the socioeconomic ladder (this of course does not solve the problem today of overqualified university graduates unable to find jobs in a contracting economy). Some barely survive the trial and emerge out of the meat grinder with mental problems or severe personality distortions, often brought on by obsessive parents who since their childhood instilled in them the idea that anything less than getting into a top university would be a family disaster. Many students who haven’t fully individuated themselves psychologically from their parents suffer crushing anxiety and guilt over fear of letting them down. Student depression is common, even before the results of the gaokao exam are released.

I wanted to know what happens to rebellious students who instinctively fight back against the harshness of the system. Because almost all of the students I taught attended good universities and thus good high schools as well, which enabled them to get into good universities, I was not able to get a clear picture about this except the obvious. The better the high school, the fewer disciplinary problems. I asked about cliques, so prevalent in American schools. There is no exact equivalent of this word in Chinese, and the phenomenon of girls being mean to girls is just not as common in China. They acknowledged bullying but had only heard of it secondhand, as something that occurred in vocational high schools. And what would happen to a female student—and the male student responsible—who got pregnant? None had even heard rumors of this happening and thus had no idea what kind of punishment would be involved. Expulsion probably, and if the parents could convince the school authorities to hush it up, an abortion and a second chance at another high school.

INFANTILIZATION OF STUDENTS

Students who wanted to have sex would have found it difficult, with so little free time and private space in which to engage in trysts. That’s why they are given no time to themselves: to preempt such threatening activities as love and sex from taking root in the first place. In this context, it is understandable, if not humane, why fully grown, post-adolescent students must be treated as children. It’s necessary to the functioning of the system, which would fly apart as soon as the students came to a collective realization that they were sexually mature adults. Since they enter college at age 18-19, as opposed to American freshmen who enter a year earlier, many Chinese students are already legally adults in their final year of high school. The system needs to brainwash them into believing they are children in order to keep their explosive hormones tightly under wrap. Indeed, until recent decades, not just high school students but university students were forbidden upon threat of expulsion from having sex. The culture is aligned to this and Chinese females in particular continue to be regarded as grown children, as “pure” and “undamaged,” until they are married. This of course shores up and benefits a sexist and patronizing patriarchal culture, quite common in the East and other traditional societies.

When I was working and living in Japan, a Japanese female office worker related to me her experience as a senior high-school exchange student in the U.S. Her American classmates told her she looked nine years old. She wasn’t deliberately acting or dressing like a child. It was unconscious—until a different culture pointed it out to her.

An anecdote will convey the heavy-handedness of Chinese high schools in the face of smoldering sexual anxiety. It took place in the early 2000s at a top “key” six-year high school (combining junior and senior high) attached to a university in Beijing. I got to know a teacher there, a woman in her mid-thirties whom I’ll call Rose, as she was attending a class of mine for a master’s program in applied linguistics for adult teachers to spruce up her credentials. Rose was a very attractive woman, with big, gorgeous eyes and a winning smile, and she had an equally bubbly, enthusiastic personality—perfectly suited to being a teacher. She was in fact deemed the best teacher of her school and had won a number of city-wide teaching awards and recognitions. What could go wrong? You might suppose a cabal of envious colleagues engineered a bogus scandal to get her in trouble, but the incident was more bizarre. She taught high school seniors. Simply for being a beautiful and captivating teacher, it was inevitable that some students would develop crushes on her. One admiring but naive female student fell in love with her began and writing her love letters, depositing locks of her hair in the letters. Rose didn’t quite know what to do with these letters; she may have sat the girl down for a private and firm talk. Somehow the principle got his hands on one of the letters. He never blamed Rose, for she hadn’t committed any indiscretion, but for the sake of all the senior students’ safety, he transferred her to teaching junior high students.

We laugh at such a ridiculous treatment of teaching staff and congratulate ourselves on our far more sensible and relaxed Western high-school systems. Yet I should add here that schools in the West used to be quite strict about sexual delinquency. My mother was kicked out of a major midwestern U.S. university in her sophomore year after being caught in a sexual relationship with another student. This was back in the 1950s, not all that far removed from our era.

HIGH SCHOOLS IN THE WEST

If I were to describe to Chinese students and educators the high school experience I went through in Canada, they would surely find it utterly depraved and dysfunctional. This was back in the 1970s at a typical, decent public high school, and I have no reason to believe things have greatly changed (unlike American high schools which have become increasingly paranoid and policed due to gang and gun violence). The students fell into two groups: the “straights” or “goodie-goodies,” who formed the majority, and a solid minority of “freaks.” I happily counted myself among the latter. It was after all the seventies, the height of liberalism and freedom. One entrance to the school building had a spacious two-story foyer, separated from the hallways by an inner set of glass-paned doors. Smoking was allowed in this foyer. Teachers could see us at a glance but never entered our space. They were afraid to, since they knew, and could smell, that we melted hits of hash oil onto the lit ends of our cigarettes before class in the morning. Those of us who were high on acid never made it out of the foyer or spent the day at the pool hall across the street. I didn’t learn much during those years nor remember ever spending time on homework, except once having to ask my mother’s help in cracking Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice.

But the advantage of comparatively lax high school systems such as in the U.S. and Canada is that it allows you to drop out, if necessary, and recalibrate before reattending later with a more mature mindset. Before my senior year, my father, a university professor, went on sabbatical to (then) West Germany and took us along for the year. I was a guest student at a Gymnasium—an academic high school for those being tracked into university. I returned to Canada the following year and completed my high-school degree part-time over the next two years, as I had to work to support myself, with much better grades, good enough to get accepted into university. Then I buckled down and studied hard, eventually earning two Masters’ degrees and a PhD from solid universities in the U.S.

The German high school experience was as different yet from the Canadian as both were from the Chinese. North American schools treat the students as budding adults, rather than children as in China and the East, as provisional, protected adults in their own ecosystem, who need a long way to go before entering the real adult world. In Germany, high schools really treat the students like adults—full-fledged, de facto adults. We had classes in calculus (of which I was so ignorant I could only use the class as German practice), physics, chemistry, biology, social studies, German, and English. Chinese high-school students get a good grounding in calculus as well but nothing serious in the humanities, nothing close to what Europeans get. In German class, we read Günther Grass’s novel Cat and Mouse. In English class, we read Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The sophistication of Huxley’s English was as hard for them as Grass’s German was for me, and I remember my classmates complaining about it to the teacher, who trudged vehemently along with the book anyway, as teachers do.

During class breaks we stepped outside to smoke cigarettes and chat with the teachers about politics and the news of the day. And everything was more political there. I was frequently pulled along when the whole school was let out to participate in some march or demonstration through the city, though I never had any idea what the protests were about. German high school students were not just allowed to engage in romance and sex; many were living together in rented rooms, with the complete acceptance of their parents. There were bars for teenagers and no regulated drinking age. Germany was and still is the most open of societies with regard to bodily freedom. One day some classmates—four girls and another boy—invited me to a Sunday outing to the countryside, where they proceeded, with complete unselfconsciousness, to strip naked and skinny-dip in the pond by where we picnicked.

Which of these three wholly dissimilar high-school systems—the Chinese, the Canadian, and the German—is the best? A question to ask is to what extent students graduating from a country’s high-school system can talk intelligently about present-day politics. And I think the German or any of the various European systems win hands down. Unless and until American students no longer need to undergo active-shooter drills to survive mass shootings, the U.S. is not morally qualified to comment on high-school education. The Chinese high-school system is probably the toughest and most totalitarian overall. But I would reiterate that the Japanese system is similar to the Chinese in many respects, with the difference that Japanese teachers have traditionally had more power over their students. A Japanese teacher friend of mine told me how he would rush to the home of any student under his charge missing class, personally drag him out of bed and march him to school. Japanese parents are required to apologize in person to the principal for their children’s misbehavior. Yet what can be said about totalitarian-style high school, oddly in its favor, is that it never wholly succeeds in crushing the students and turning them into mindless robots. I have met countless Chinese and Japanese who have gone through the system and turned out just fine, their imaginations and creativity intact. The only real major criticism, as elsewhere in Asia, is the system’s failings in teaching English.

THE CONFUCIAN QUESTION

An intriguing article by a Chinese Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, entitled “Language as play: Why Chinese students study hard but speak softly,” argues that a Confucian-based education in which student silence is seen not as a problem but as normalized behavior is primarily to blame for poor English proficiency among the Chinese: “In East Asia—China especially—this restraint is cultural. It flows from a Confucian inheritance that prizes discipline and harmony over spontaneity. Education is moral formation before it is communication. The ideal student is diligent, modest and self-controlled….The cost is emotional as well as linguistic. Language becomes an exam subject, not a living bond.” This idea is hardly new. Chinese educators have long acknowledged that the teacher-centered language classroom is fundamentally at odds with language learning, even as major reforms never materialize. What’s interesting is the author’s focus not simply on the importance of oral communication but on play itself as a means to this, holding up the casual classroom talk of African students in Moscow learning Russian as an example for the Chinese to emulate.

What I would like to zero in on is something else: the rigidified, essentialized concept of Confucianism as an inviolable feature (or roadblock) of Chinese education. This timeworn and clichéd version of Confucianism, unthinkingly shared by many Chinese, represents the most calcified and frightful form of patriarchy ever devised. Developed through twists and turns over the millennia, with the historical figure of Confucius long left behind, it consists in a nested, military-like framework of control operating at all levels of society, from the emperor down to the family itself, with the father receiving automatic obedience and respect from sons, elder sons receiving the same from younger sons, and all males in the household receiving the same from their mother and sisters.

In the traditional Confucian classroom, the teacher’s role is to command the same obedience and respect from the students. Since obedience for its own sake is paramount, anything of truly pedagogical concern is incidental and irrelevant. To be sure, this caricatures what actually goes on in the classroom, but it nonetheless forms the ideological ground on which genuine learning must exert itself. It also has little to do with Confucius, according to scholar Chen Jingpan. In his classic English introduction, Confucius as a Teacher: Philosophy of Confucius with Special Reference to its Education Implications (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1990), Chen reminds us that Confucius prioritized not obedience but study (xue) and questioning (wen)—with an emphasis on questioning as a means of mutual enlightenment. Real learning occurs only when students are given the space and initiative not just to listen but to communicate critically through dialogic interaction. Far from a stern authoritarian, Confucius was the Asian counterpart of Socrates and the Socratic method of learning. Sheer obedience is irrelevant to learning. It is only an exaggerated notion, deriving ambiguously from filial piety (xiao) in the domestic sphere—respect for one’s parents and ancestors.

My Chinese students were all steeped in Confucian precepts, though they had quite varied responses to which precepts seemed most vital to them. Some mentioned the importance of being polite and respectful, others diligence in study, and others still social harmony and collectivism. Some simply reiterated the five traditional Confucian virtues of benevolence (ren), righteousness (yi), propriety (li), wisdom (zhi), and spiritual piety (xin). Confucianism finally is whatever the student makes of it. Chen notes that benevolence is mentioned in Confucius’s Analects far more than the other four and is the controlling virtue from which the other virtues flow. Besides the English term benevolence, ren can also be rendered as agape (unconditional love), generosity, sincerity, earnestness, kindness, humanity, philanthropy, and empathy, or in Chen’s definition, “an earnest desire and beneficent action, both active and passive, for the well-being of the one loved.” An interpretation of Confucius giving precedence to benevolence is at odds with the usual notion of stern respect for and humble supplication to authority. Benevolence implies mutual humility and the fostering of well-being to bring people closer together as equals. It also has more in common with the student-centered than the traditional teacher-centered classroom.

But is Confucianism necessary at all to explain Chinese education? It seems rather superfluous when you get down to it. Whichever Confucian precept one wishes to belabor—diligence, questioning, propriety, wisdom, harmony, respect, benevolence—more or less the same virtues are taken for granted in education the world over. One could just as easily call them Christian virtues, or good old Puritan virtues, or communist virtues for that matter. Regardless of what it actually means upon analysis, Confucianism does have the benefit of giving Chinese students a sense of historical and spiritual grounding in their culture. It also conveniently serves, in the classroom context, to remind students that they are situated in an educational community that involves collective responsibilities. Confucianism is not some special quality that only the Chinese and other East Asians embody, while the rest of the world flounders in moral confusion. It’s standard pedagogical philosophy and common sense.

A word on Asian student silence. There is no single explanation for the dogged phenomenon. Some blame Confucianism: the belief that one should not speak up even when prompted, because it’s not the student’s place to speak up. Combine this with reluctance to show off among one’s peers. Many students, in the West as well, simply aren’t sure of the right answer. But the best explanation, in my view, is youth. Teenagers tend to be intimidated in formal settings, no matter how relaxed and cheerful the teacher. I spent years trying to figure out how to get my American freshmen to speak up in class. Conversely, the older the students are, the more talkative they are. Some of my most garrulous students were adult Russian refugees in oral English classes in the U.S., even though their knowledge of English was practically nil. I’ve taught working-adult students in China as well. They converse readily and are a joy to teach.

UNIVERSITY: DORM LIFE

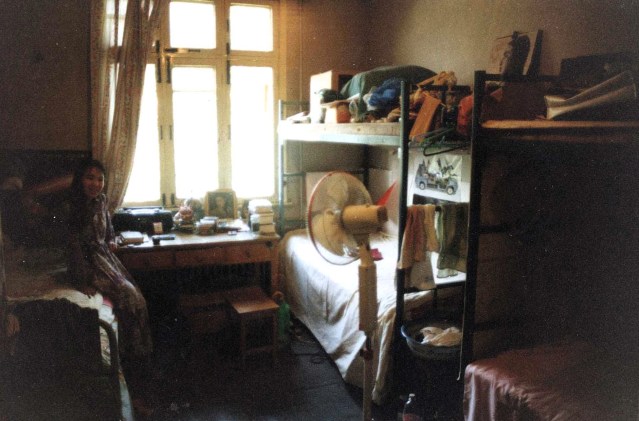

Chinese universities don’t have fraternities or sororities, and it’s still uncommon for students to live off campus. With no tradition of off-campus partying, except for occasional restaurant or KTV outings, Chinese students are accustomed to a much more sheltered and sedentary lifestyle than university students elsewhere. In the 1990s, student dormitories were crowded and stuffy, with barely enough space to walk around. Typically, eight students slept in four bunk beds and shared a single table in lieu of individual desks. Until recent years, electric kettles and hot plates were prohibited in dorm rooms due to limited electricity and fire hazards; large thermoses supplied hot water for drinking. There was no air conditioning in hot weather, and lights were shut off at eleven PM. Bathing took place in the campus public shower, and students had to pay for shower tickets.

Accommodation today has vastly improved. Most dorm rooms now have their own shower stall, air conditioning, and loft-bed units with a desk under the bed. Four to six students share a room. As in the past, male and females are segregated either on different floors or in separate buildings.

The biggest complaint about dormitory life today is that male students have a penchant for turning their rooms into pigsties. This is the Chinese version of freshman rebellion, equivalent to American frat boys waking up in their drunken vomit. As a rule, science, technology, and engineering universities and departments are male dominated, while females dominate business and the humanities. In foreign-language and teacher-training universities, 80-90% of the students may be female. In fields where English is important or is itself the major, the shy and self-conscious male students huddle in self-protective solidarity around their own table or in the back of the classroom. They rarely speak up, more mortified by their linguistically superior female classmates than by their teacher. Many give up trying to compete and just go through the motions, striving only to earn grades high enough to pass. High-achieving students in the male-dominated technical fields are a different matter; they are the nation’s future and success story. They are the ones designing the world’s most advanced infrastructure—China’s wind and solar-energy fields, towering bridges, high-speed trains, luxury EVs. But I’m referring to a male-student conundrum I have frequently encountered as a humanities teacher. If they happen to be Party members or have been spoiled by well-connected parents, they won’t have trouble finding a job after graduating anyway. Combine this casual attitude toward their education with the explosive freedom of their newly won independence from their high-school incarceration, and the dorm itself turns into a morning-after frat house.

In my latest Chinese university job in the 2020s, I was a personal tutor to close to a hundred freshmen students. The most common complaint by the males was filthy, academically underachieving roommates who gave up from the get-go, in their first semester, and wallow in video-game addiction. They leave their room only to go to class or pick up food deliveries from the nearest campus gate, easier than walking all the way to the campus cafeteria. Garbage in the room accumulates and the odors become horrific. Clothes are never washed but worn until they disintegrate. Some never bathe. Official student teams make spot checks on dorm-room hygiene merely to be blown back by the stench when they open the door. Studious roommates can’t sleep well from the noise and flashing lights from all-night gaming sessions. If quarreling doesn’t get anywhere, as a last resort they can apply to change dorm rooms, at the risk of finding the new dorm-room situation even worse. Or they move off campus to find peace. In every class, I had male students regularly walk in late in a daze. They would spend the first hour of class trying to orient themselves, whispering to their adjacent classmates what they were supposed to be doing. Constantly short of sleep, they struggled miserably to stay awake. They hated to be there and were hard to teach, to say the least.

Female students on the whole seem to survive the high-school experience better and emerge more intact. No need to sabotage their university education with chaotic acting-out. They are all addicted to their cellphones, but the girls generally get along better with their roommates and get better sleep. They are far more sanitary, collectively working a system for removing rubbish and hitting the lights and the noise at night. They bathe. Some turn their dorm room into their online-business office, stocking the space with their inventory.

The “four-year vacation” of college, after the six grinding years of secondary school, is a term I first heard bandied about in Japan, which also has a career-determining university entrance exam similar to the Chinese gaokao. Japanese high-school students complained to me that they rarely had a full night of sleep during their final year or two of preparation for the exam. Evening cram school was de rigueur. After going through this “examination hell,” you can imagine what university feels like when for the first time in your life, you’re away from teacher surveillance and aerial objects like helicopter moms. To some extent the same occurs everywhere. I have an American cousin who doesn’t remember anything about his first year of college because he was continually passed out drunk in frat-house parties. I don’t recommend this, though I can understand it.

Not every student blows off their college years. Most get their act together and buckle down. American students have more reason than most to be serious about study, with astronomical tuition fees at U.S. universities. Flunking out means throwing away thousands of dollars of their parents’ money in wasted tuition. If you’re going to flunk out, do it fast—in the first semester—to stop your financial hemorrhaging! Travel the world, get a job for a few years, or go into the army! Come back to school when you’re ready. The U.S. university system is cleverly structured to make a lot of money off dumb students. It’s the reverse of the Asian system. Instead of grinding high school years followed by a four-year vacation on a college campus, American students who have not had the benefit of a good highschooling find themselves in a four-year nightmare. Many simply aren’t prepared for study. Only 55% of undergraduates at U.S. universities complete a four-year degree after four years; the percentage rises to 65% after eight years. That is, some get out early and return to university years later, now more mature and studious, to finish their degree. Still, one third of American bachelor students never finish their degree.

ADMINISTRATIVE HURDLES

Marched through their four years in lockstep, Chinese students don’t have the luxury of escaping and finishing college later. Since they all enter the job market upon graduation as the same cohort, and prospective employers expect this, those who take time off, even just one or two years, are passed over as already “old.” In China, 90-95% of undergraduate students complete their degree in four years.

In years past, it was closer to 100%, with a bit of fudging by school administrators and parents with good guanxi, or connections. I once failed a senior student at a top Beijing university who showed up to class for the first time in the semester on final exam day. Her parents had the failing grade changed to a passing one in back-room dealings I was not a party to. At another university in the mid-1990s, a graduating student asked me to write her a recommendation letter to a U.S. university where she was applying to study abroad. As some of her course grades were wanting, she told me quite frankly that she went to the campus office and got the staff there to print out a new transcript with the grades changed to order. Over recent decades, Chinese universities have been straightening out such flagrant practices, but guanxi is always important, and parents routinely curry favor with influential professors and administrators with monetary gifts.

The problem for foreign teachers in Chinese universities is not manipulated graduation rates or back-room shenanigans. Why in the world would you bang your head on the wall over academic dishonesty that doesn’t concern you? It’s enough to be a good teacher and do your job, treat your own students properly, assign grades fairly, and don’t worry about what may happen to the grades after you assign them. The problem with regard specifically to foreign teachers is that Chinese university administrations don’t have a stellar reputation for treating us well. This has a long history going back to the country’s uneasy, suspicious relationship with foreigners in its domain since the 1950s. For anecdotes and examples, see my essay, The Chinese university: A primer for prospective foreign teachers.

This, again, is improving. In the mid-2010s, the Chinese Government started requiring all foreign teachers to prove their credentials with third-party verification of their diplomas and home-country criminal-record checks (e.g. FBI check in the case of U.S. teachers), to be further authenticated by the respective country’s Chinese Embassy. In demanding qualified foreign-teaching staff, universities for their part began to demonstrate correspondingly more commitment and professionalism toward their foreign faculty. Yet foreigners are still and will always be regarded as outsiders. Senior Chinese faculty are invariably Communist Party members, and every university has a Party office overseeing everything. Virtually every decision in every departmental meeting needs Party approval. Every new foreign hire must be signed off by Party staff in the university’s Foreign Affairs Office, overriding the department’s recommendations if it so chooses. Foreign teachers are invited to departmental parties and events for hospitality purposes but not to department-wide meetings. Even if the foreign faculty were fluent in Chinese, they would neither be welcome nor given any say. The Chinese public university remains a closed system.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the following teachers for the information they provided on Chinese education: Feng Yihan, Hu Xiaoyu, Wu Linna, Gao Mingzhe, and Zhang Weiwei. And to the following students for their equally informative insights: Wang Qingyi, Zhou Ziyue, Wang Xiaohan, Lei Ziyuan, Guo Peiyan, Liu Xiangying, Yang Jingjing, and Emily Chen.

* * *

Other posts in this series:

Insights into China, Part 1: A walk down the street

Insights into China, Part 2: A meal in a restaurant

Insights into China, Part 3: A stay in a hotel

Insights into China, Part 4: A visit to the library

Insights into China, Part 5: An invitation to a party

Insights into China, Part 6: An afternoon in a café

Categories: China