View of Yellow Crane Tower in old Wuchang (photo by Isham Cook)

A walk down old Wuchang’s Tanhualin historic pedestrian street takes you past boutiques, cafés and nineteenth-century Western consulates and missions, before ending at grimy Deshengqiao, more alley than street, where a left turn plunges you into a more authentic China of milling crowds and open-front shops selling fish, vegetables and hardware items, a timeless lane because it couldn’t be more ordinary. A right turn further down and you’ll see the high school I’ve visited on numerous occasions involving an English-teaching business I won’t go into here. Street-side stands sell deep-fried chicken patties injected with processed cheese, a popular snack with the students. Further on south is the landmark Yellow Crane Tower, dating to the third century AD, destroyed and rebuilt countless times. It once overlooked the Yangtze River; its present incarnation sits a kilometer inland. Like almost all Chinese cities, Wuchang was once walled. City walls were employed to protect the inhabitants, but in September of 1926 the walls turned the city into a death trap when it was shelled by the Kuomintang Nationalist army and the warlord in control of Wuchang, Wu Peifu, requisitioned all food supplies to the army. The siege lasted six weeks and thousands are thought to have died of starvation, judging by the many bodies witnessed being tossed over the walls. An all-too-common occurrence: most civilian deaths in wartime China were due to famine or deliberate starvation rather than guns or bombs; the siege of Changchun by the Communists in 1948 starved 150,000 civilians to death. The wall exists no longer, and the moat that once surrounded it is now Zhongshan Avenue. Most residents probably couldn’t care less. Old Wuchang is a mere afterthought amidst the vast urban sprawl of contemporary Wuchang, which along with Hankou and Hanyang across the river form the megacity of Wuhan (pop. 11 million; unofficial pop. 20 million), the largest city in Hubei Province and one of the largest Chinese cities you had never heard of until the 2020 coronavirus outbreak.

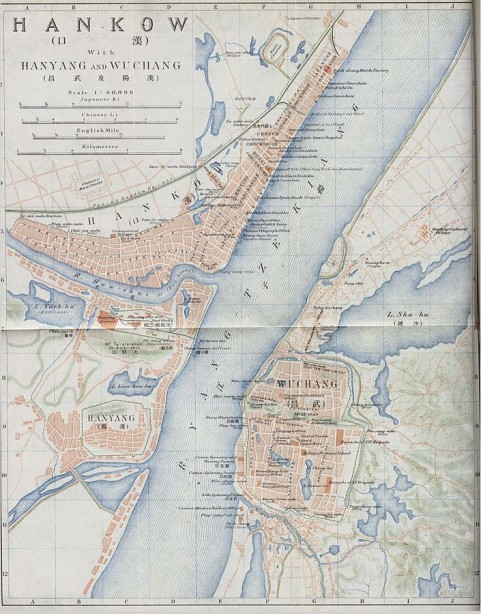

Hankou is the most bustling of the three cities. Many of the stately buildings of the former British, Russian, French, German and Japanese concessions still stand. Now interspersed with elegant restaurants, the riverfront has some of the feel of Shanghai’s Bund. I have walked the 3.5-kilometer stretch of the Hankou Bund many times. Between the main boulevard and the river is a pleasant park built on reclaimed land; there is a ferry for crossing the river. A steady procession of cargo ships passes daily and well into the night, with bats flying about. In the autumn of 1926, while Wuchang was being shelled, you saw a very different sight. Spaced along the river facing Hankow (as it was then spelled) were British and American cruisers and destroyers pointing their six- and eight-inch caliber guns down the streets as a warning to would-be Chinese rioters. If you happened to angle one of these guns upward and fired it, the shell would have sped past the rear wall surrounding the concessions, once again now named Zhongshan Avenue (the Communists’ favorite street name), and the parks and sports clubs beyond (which up until a decade ago had been a warren of unmarked brothels whose sliding doors revealed, to my curious eyes, girls on sofas in gaudy lingerie), and well past the Second and Third Ring Roads to land somewhere between Jinyin and Dugong Lakes some fifteen miles to the northwest. If instead you fired the gun straight into the concessions, it would have cleared the rabble all right, so effectively that much worse rioting would likely have followed, defeating the purpose. Not that there wasn’t precedent for the use of heavy guns on massed crowds. Back in 1842, with just three rounds of a howitzer at close range, the British turned a street in Ningbo packed with hundreds of Qing troops into a “writhing and shrieking hecatomb” (Julia Lovell, The Opium War).

Hankow and Wuchang, 1915 (https://goo.gl/9H2vmu).

The timeworn suspicion and contempt the Chinese felt for the outside world only deepened over the century the Yangtze was controlled by Western warships, 1842–1949. Stray yangguizi, “foreign devils,” were “constantly under menace from local populations who—given the slightest opportunity—would kidnap, mutilate and murder foreigners who wandered more than a safe distance” from their camps or concessions (Lovell). The hostility flared up in periodic attacks and massacres, notably the thousands of Western soldiers and civilians killed, along with tens of thousands of Chinese Christians, in the Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901. Things remained tense even after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 and up through the outbreak of war with Japan in 1937. But anger toward the West often coincided with the far greater viciousness of Chinese-on-Chinese violence.

Certainly, over the recent decades, China’s political stability, economic growth and maturing international outlook has greatly improved life for everyone, domestics and foreigners alike. The old hatreds and suspicions have largely died down, we hope for good, with more recent outbreaks of anti-foreigner violence, such as the 1988 Nanjing riots against African students (after some had been seen cavorting with local women), now quite rare. For the first time in China’s history, we can safely wander its streets at leisure. Thugs are still known to rob drunken foreigners outside bars at 3:00 am, but the problems we encounter these days are trivial by comparison—the company that doesn’t pay your final month’s salary, or the landlord who likewise disappears with your security deposit when they know you’re leaving the country. I’d rather be living in China now than in 1926, when we observe one foreigner struggling with his luggage in Hankow’s British Concession after refusing the rickshaw drivers’ outrageous fees, as described in Richard McKenna’s The Sand Pebbles (Harper & Row, 1962):

They walked along Honan Road. Rickshaw coolies cursed them in English and Chinese….A fat White man up ahead was having it even worse. He was carrying a heavy suitcase and losing face with every step. He wore a straw hat and he was sweating through his white coat. His left arm stuck out stiffly, to balance the suitcase. Yapping coolies followed him. One ran and kicked the suitcase and it spilled open. The coolies began snatching and throwing socks and drawers and paper. They were not stealing it, they were just throwing it around. The man went to his knees, trying to grab his gear and repack it. A laughing crowd formed.

Note that this was the British concession, subject to British law. The Sikh policemen hired to keep order stayed out of the way, mindful not to incite the mob over petty matters, who could easily and often did get out of hand, for there were plenty of volatile Chinese laborers around. Foreigners were discouraged from venturing outside the concessions into the adjacent “native city,” where they risked being outright assaulted or worse, and where the protagonist seaman Jake Holman and shipmate Frenchy Burgoyne of the U.S.S. San Pablo would steal under cover of darkness, armed with revolvers. They were looking after the Chinese girl Maily, whose freedom Burgoyne had purchased from a riverfront brothel in Changsha but had been prevented from marrying under miscegenation laws.

The menacing atmosphere of the The Sand Pebbles is well captured in the feature film (1966, dir. Wise). I first saw it as a child and it has long haunted me, above all the scene in the Red Candle sailor bar in Changsha. The beautiful Maily (played by Thai actress and uncanny Gong Li lookalike Marayat Andriane) is stood on a table and auctioned off to the highest bidder. You may recall it, as her dress is rolled higher up her thighs with each bid to the chants of “Strip her! Strip her!” and is then ripped off her shoulders (in the novel it’s torn down to her hips), before mayhem breaks out and Holman and Burgoyne manage to ferry her away to safety. For cinematic purposes the love story is simplified and compressed. A local family take her in. Burgoyne sneaks off the ship and swims across the freezing river to visit her one night and dies in her arms of exposure. When Holman finds Maily with the dead body, they are surprised by nationalist militia, who kill Maily as Holman escapes through the window.

The novel’s version of the events are at once more mundane, pathetic and moving. Maily is not killed but is smuggled to Hankow, where through a local contact Burgoyne is able to rent a room in the native city, “above a kind of hardware store, with the stairs inside. It was small and shabby and the single window had no glass. Holman opened the wooden shutter and looked down into a short blind alley filled with beggars.” With a “clay stove and a rickety table” the room was “dismal,” while “bright scraps of cloth” are hung up to offset the brown wallpaper hanging off the walls. There are other telling details:

When Maily served the food, it was rice and fried peppers and pork in gingery sauce….They had only the chair and chest to sit on, so Maily ate standing, bowl and chopsticks in hands, like a Chinese woman. She brought them acrid Chinese wine, heated. The hot food and wine made the room steamy warm and good-smelling.

The only problem is, contrary to the film, Maily not only does not love Burgoyne, she isn’t even attracted to him. It’s Holman she wants. Loyalty to his friend and other inner conflicts prevents him from reciprocating. Neither has the guts to tell Burgoyne. Burgoyne does make that final swim ashore and is found dead by Holman, watched over by a Maily in a deserted alley. That’s the last we hear of her.

McKenna’s popular novel has much to commend it, above all the richly observed period description. It was a deft move to set the story ten years before the author himself was stationed in Hankow and Changsha in a U.S. gunboat, at that flashpoint moment of 1926 and early 1927 when the Nationalists kick out the Communists and Wuhan is a microcosm of the country as a whole, the river a microcosm in its own right with two great antagonists thrust together on a symbolic stage, the Chinese shoreline, so near yet so far away, with its barrier of junks and screaming students and nationalists hurling refuse at the American vessel. One day appears a bizarre procession of angry, stark naked Chinese college girls. They don’t quite get their point across to the mind-blown San Pablo crew, who have been confined to the ship for months and denied their whores (the story is too unbelievable not to be true, though the tradition of female protest nudity can be traced back to the Shang Dynasty).

Nineteen thirty-six too was a tense, key year. Despite the return of the international concessions to the Chinese, as long as the gunboats remained on the Yangtze so did the anti-foreigner enmity, albeit this was shifting to the Japanese upon their escalating attacks on Shanghai and other cities; in 1938 Wuhan would see calamitous war and half a million dead. The Hankow of 1936 would not have appeared all that different from that of a decade earlier: the same bars, the same tales and gossip, the same glimpses into life outside the concessions, an era so mysterious and entrancing now; and the same forlorn females to be wooed or rescued by expats, upon whom McKenna must have modelled Maily and Burgoyne. But even writing in retrospect in the 1960s, the author was unable to surmount the entrenched stereotype of the doomed interracial expat relationship. The very subject matter necessarily plunged his story into the realm of tragedy. The novel’s ideology further required that Maily be tainted, her fate sealed at the outset, by her status as prostitute, even if an enslaved and victimized one. It’s easier to make a character go away and the audience to forget her, if she has known low society.

With Richard Mason’s The World of Suzie Wong (Penguin, 1957) the expat-prostitute relationship is freshly conceived, and we emerge into the sunnier world of comedy. There are several factors enabling this. Mason sets the story in postwar Hong Kong, but the details of the setting are drawn from his contemporary experience of the city a decade later. We are also in relatively free and safe British territory: no fearsome walled or “native” city, no dangers or threats, no need to be armed. When the protagonist Robert Lomax first arrives on Hong Kong Island after crossing over from Kowloon by ferry, he is politely told there are more appropriate places for a gentleman to stay than in the seedy district of Wan Chai. Lomax heads there anyway and picks a hotel at random, the Nam Kok, which turns out to have a lively sailor bar.

The bar’s most popular girl is a Shanghainese who fled the chaos of the mainland, Suzie Wong. She lives with her baby in a shanty not far away and is seen coming and going daily. Significantly, she’s not enslaved or confined but has freedom of movement and plies her trade by choice. Unlike the Red Candle in The Sand Pebbles, the Nam Kok is not a brothel. In fact, to maintain appearances the hotel forbids sex workers from entering the bar unless accompanied by a male. (Wan Chai today is no longer seedy, at least in one sense of the word. It’s clean, orderly, with gleaming office buildings and respectable English pubs. On my last stay in the city, the women riding the elevator in the hotel on Hennessy Road were locals, not mainlanders, judging by their Cantonese and their poise; one had a see-through blouse and an areola that peeked out from the edge of her bra. They got off on the third floor, which had a single door and a “Members Only” sign.)

The setting is playfully raucous and comic, and Mason conveys the idiom of the times in all its chauvinistic quaintness. Suzie is seen frolicking with a drunken American sailor, who “had been seized by sudden violent passion and was thrusting her back into the corner to kiss her and the girl was struggling, though only half-heartedly as if she found it no more than tiresome. There was not much to be seen of her but her kicking legs and her thigh through the split skirt.” Lomax remarks with a laugh, “Well, she’s got beautiful legs, anyhow.” To which the girl opposite him replies, “But don’t you think she is the prettiest girl in the bar?”

Though a bestseller at the time, the novel has not been regarded as particularly funny by subsequent audiences, notably feminists. Part of the problem is the language, the penchant for referring to Asian females as “little” and similar diminutives. To list a few examples: “‘It’s that little bitch of mine. She’s with a sailor’”; “There had been lashings of whiskey to wash down the fabulous food, and the usual little Chinese hostesses to joke and flirt with the guests”; “The tiny luscious Jeannie came out, ushered by a gangling American sailor”; “An elderly amah with tiny slit eyes and huge prognathous mouth with gold teeth.” And my favorite: “the little blown-up football of a Suzie had appeared.” It wasn’t just Mason; the vernacular was widespread. Time magazine wasn’t immune, describing Nancy Kwan, who played Suzie in the feature film (1960, dir. Quine) as a “Wonton-sized” 5 ft. 2 in., 104 lbs. and “the most delicate Oriental import since Tetley’s tender little tea leaves…the new ‘yum-yum girl’ has saved the movie” (April 11, 1960).

In one scene, the Englishman “that little bitch of mine” Ben impersonates a policeman and kicks open a door at the Nam Kok to catch Suzie in a room with another American sailor: “Ben leaned over without effort and caught her ankle. He dragged her back across the bed like a lizard by its tail [and] began to spank her. He spanked her long and hard…Suzie lay there crying like a child.” It should be noted that that decade indeed had a thing about spanking. I recently chanced upon a 1950s New York Daily Mirror clipping entitled, “If a woman needs it, should she be spanked?“, inviting male readers to opine on the topic. All were unanimous: “Why not? If they don’t know how to behave by the time they’re adults, they should be treated like children and spanked. That ought to make them grow up in a hurry.” “Yes,” another wrote, “most of them have it coming to them anyway.” For Suzie, the spanking was “one of the proudest events of her life.” But soon she leaves Ben for Lomax. He himself refrains from properly putting her in her place, causing Suzie some consternation. He seems torn: uneasy at the established practice of spanking and beating yet not altogether critical of it.

All this, of course, was guaranteed to turn the novel and the moniker “Suzie Wong” into a signifier of White misogynist racism, and perversely, a certain exotic chic, e.g., the Beijing nightclub called Suzie Wong that drew brisk business in the early 2000s (until shut down a few years ago ostensibly for a neighborhood renovation). The feature film of Amy Tan’s novel The Joy Luck Club (1993, dir. Wang) spread the message by lambasting the Suzie Wong movie as a “horrible racist film.” Nancy Kwan had actually been invited to play one of the mothers in The Joy Luck Club but turned down the role when they refused to excise this line. It’s all a bit ironic and unfair, since the movie greatly toned down the sexist language and violence of Mason’s novel. There are no spanking scenes or turning girls upside down in their bar booth; Kwan’s Suzie gets roughed up by a sailor at one point but fights back. Fans of the novel cite its charm—Lomax’s earnest love of Suzie, his capacity for introspection, his commitment and marriage to her—and its progressive vision of interracial coupling in a racist milieu. True, he’s not even sure why he’s marrying her. A voice inside him nags: “‘Don’t be a fool—you know you’ll regret it! You only want to marry her because her ignorance inflates your ego—because she makes you feel like a god.’ ‘Well, what’s wrong with that?’ I asked the inner voice defiantly.” In England where they settle and where in the 1940s–50s they would have presented quite a sight, she acquires in his eyes a quiet dignity: “Soon she was sitting up proud and straight in the Chinese way…and she looked so proud and poised as we entered the gallery [where Lomax’s Hong Kong paintings were on exhibition] that you would have thought twice before calling her a whore.”

If the idea of “Suzie Wong” still attracts ire, long after this minor novel from a bygone era jogs few people’s memories, it must have something to do with the name itself, the power retained in the name. Susan, a common English female given name, is yoked to one of the most common Chinese surnames. From old Hebrew Shoshanna and later Suzanne and originally evocative of purity (the Persian lily flower), it’s now whorish sounding in its unnatural juxtaposition. What is the allure of “Suzie” which makes it any better than her native Mee-ling (Mason’s spelling of 美玲, “beautiful jade”) or Mei-ling, in the correct transliteration? We can hardly imagine the novel having as much appeal had it been entitled The World of Wong Mee-ling. Is it that the inscrutable language is all too complicated for us? Is it only a matter of clarity, to gender the name so that English readers know it’s about a woman? Or is there something more nefarious going on in the symbolic act of renaming, to remind the subjects of the formerly occupied country that they can never remove the traces of their colonization, that the name cannot be uttered without having the illocutionary force of a summons (“Suzie Wong!”)? The Sand Pebbles represents an earlier era, before this business of substituting English for Chinese names began, but Maily the brothel slave is shorn of her native name as well, inasmuch as it’s been anglicized and domesticated for Westerners: it could be an English female name (the original is presumably 美丽, or Mei-li), while her Chinese surname is simply excised.

More to the point, is there something threatening about the Chinese female who assumes an English identity? The Hong Kong Chinese have long done this (the present Chief Executive Carrie Lam, the actress Maggie Cheung), but we don’t seem bothered when Hong Kong males adopt English names (Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan). Yes, they all have their native names as well, and their unaccountable habit of putting the surname first. Today on the mainland too it’s common practice for students to adopt an English first name, again for the reason of taking on an English persona, but also to make it easier for foreigners they come into contact with to say their name (some Chinese phonemes are unpronounceable to people unacquainted with the language). In any case they don’t have a problem with adopting a dual identity, Chinese and Western. And I wonder why it is that we have a problem with it. Could it be that the vague discomfort the Anglo world experiences at the sound of “Suzie Wong” is indicative of its own racism, as if it’s felt the Chinese do not have the right to an English name? Or to put it more bluntly, that Lomax has no business mixing with people outside of his race, and neither does Suzie?

One of the covers of the Emmanuelle series, this one showing the author.

On the subject of names and naming, it gets more complicated still in the case of our next author, Emmanuelle Arsan. Born Marayat Bibidh into a wealthy family in Bangkok in 1932, she was by her own account highly sexed from childhood. At the age of sixteen while attending school in Switzerland she met her future husband Louis-Jacques Rollet-Andriane, a French diplomat fourteen years her senior. They fell in love and it’s assumed she lost her virginity to him at once, but they held off marrying until he secured a post with UNESCO in Bangkok eight years later. There they mingled with the expat jet set and made the acquaintance of the Italian aristocrat and libertine Prince Dado Ruspoli. They fell under his spell and were indoctrinated in his ideas on sexual freedom. The trio became inseparable. There were freewheeling parties and orgies and frequent trips between Bangkok and Paris. Three years later, in 1959, Marayat and Louis-Jacques published a novel anonymously in France entitled Emmanuelle and circulated it privately among friends. It’s understandable they were cautious about publicizing the book at the time. It’s a shocking read and more importantly, well written, which makes it even more shocking.

The semi-autobiographical novel recounts Marayat’s sexual coming of age, and I don’t mean losing her virginity, but becoming liberated to a radical extreme, with acts of outrageous, if fictionalized, public exhibitionism. A few real-life details are altered or reversed. Emmanuelle’s husband is a Frenchman named Jean who is already established with a job and house in Bangkok, while Emmanuelle herself is French, not Thai, and arrives there for the first time to join him. There is a literary tradition of trains and planes symbolically serving as vehicles of sexual transport (D. M. Thomas’s The White Hotel comes to mind), and the excesses begin on the flight to Bangkok. Emmanuelle is in a curtained-off first class cabin; next to her is a man and across from them an English boy and girl, both “only twelve or thirteen.” The lights have been dimmed; she is touched and fondled by the man; he pulls out his penis and ejaculates over her. She receives the “long, white, odorous spurts…along her arms, on her bare belly, on her throat, face, and mouth, and in her hair.” Suddenly the lights come on as the plane starts its descent. The stewardess steps inside and she and the two children, who were “less than three feet away,” stare at the semen-splattered Emmanuelle: “She looked at the damp spots that spread out in both directions from below her collar. She rolled back the lapels of her blouse and the pink tip of a breast appeared. Her neckline remained open and four pairs of English eyes were glued to the profile of her bare breast.” The stewardess helps clean her up in the kitchenette, whereupon Emmanuelle is fucked by a handsome steward—all before the plane lands.

The next portion of the story involves Emmanuelle’s lesbian encounters at an exclusive sports club in Bangkok’s foreign community, including one precocious thirteen-year-old who instructs the heroine on the art of public masturbation (to a select audience). Emmanuelle spends much of the latter half of the narrative with Mario, a wealthy Italian expat modeled after the Prince Dado Ruspoli, who tutors her in his erotic philosophy. His discourses supply the theory to the sexual practice of the novel’s former half. There are quotable lines like, “Your horizon will always be shamefully restricted if you expect love from only one man”; “Adultery is erotic. The triangle redeems the banality of the pair. No eroticism is possible for a couple without the addition of a third party”; and “A woman who makes the first move, at a time when a man isn’t expecting it at all, creates an erotic situation of the highest value.”

Bangkok is often regarded as the Amsterdam of the East not only for its red-light districts but also its canals, the best known being the Klong Saen Saeb, a shabby experience for first-timers but whose mysterious lairs and lodgings along the banks grows on you and makes it one of the most romantic canals in the world. One of these lodgings is Mario’s residence in the novel. Another is the famous house built in 1959 by the American architect and designer Jim Thompson; the intrigue around his disappearance in 1967 has helped turn his house into a major tourist attraction today. He was possibly known to Marayat and Louis-Jacques back in the late 1950s (more research needed here); the couple was well known and notorious for their sex parties, indeed singlehandedly gave Bangkok a reputation as one of the first locales for swinging.

The canal and its exotic atmosphere is nicely captured in the Emmanuelle film (dir. Jaeckin, 1974), with a screenplay by the author and Sylvia Kristel in the main role. The film was hugely popular and spawned numerous sequels, but I found it disappointing and lacking next to the novel. While there is plenty of nudity, explicit sex, so essential to the story, was unfeasible at the time. The film needs to be remade in an X-rated version that’s true to the novel, by a daring producer or director with a proper budget and better acting. But I’m jumping ahead.

The popularity of the novel as it privately circulated among its decadent readership convinced the couple to have it republished under the author’s nom de plume, Emmanuelle Arsan, in 1967 (Grove Press came out with an English translation in 1971). By this point, Arsan had ventured into acting, and her beauty had gotten Hollywood’s attention. At the seasoned age of thirty-four, she was offered the role of Maily in The Sand Pebbles, under her cinematic name Marayat Andriane; Chinese actresses were hard to find and a Thai actress would have to do. She’s nonetheless memorable in the role, but not for the reasons intended, for while her character is the epitome of tragic female virtue, belied by her smoldering eyes, the actress herself was one of the indelible faces of the sexual revolution—or depravity, depending on where you’re coming from. Hollywood prudery allowed her dress to be yanked off no further than her shoulders and a full slip revealed underneath, but she would have had no problem being stripped naked. After all, in the film she herself later directed and acted in, Laure (1976; based on her novel of the same title), she engaged in sex scenes in full-frontal nudity.

The ironies abound. The director of the Suzie Wong film, Richard Quine, had a terrible time convincing Nancy Kwan to wear a half slip and bra rather than a full slip in the scene where an angry Lomax rips off her Western-style dress (she relented). Not that Kwan’s reputation was unblemished; she was rumored to have had a fling with Marlon Brando, who had driven the actress originally given the Suzie Wong role, the French-Vietnamese France Nuyen, to a nervous breakdown.

Arsan was rumored to have had her own affair with Steve McQueen, and the delectable possibility is that it was sparked by their joint reading of the novel, in which, as recounted above, his character Holman was the real object of Maily’s passion.

Eventually it came out that Arsan’s husband Rollet-Andriane was the author of Emmanuelle. He had apparently used her name as a cover to protect his working reputation. Just as likely, they collaborated on the story and he polished the French, or it was a three-way collaboration with Dado Ruspoli; it’s hard to imagine she had no input into the novel. In this new configuration, “Emmanuelle Arsan” is more of an authorial idea, or ideal, than a person, as well as the deftest of marketing ploys—the Oriental femme fatale authoress—to captivate a prurient audience. It worked, and the reclusive couple cultivated their enigma and mystique to the end, sheltering themselves in a retreat in the remote French countryside from the 1980s (Arsan died in 2005 and Rollet-Andriane in 2008). For my part, I can no longer watch Marayat Andriane, or Emmanuelle Arsan, or whoever this figure as elusive as a female in a Picasso painting is, play Maily in The Sand Pebbles without imagining her thirsting for jets of semen to the chants of “Strip her! Strip her!”

In the same year Rollet-Andriane arrived in Bangkok to marry the twenty-four-year-old Marayat Bibidh, a curious novel entitled A Woman of Bangkok (Secker & Warburg, 1956) came out by an Englishman, Jack Reynolds. It’s in some ways even more striking and shocking than Emmanuelle, though for different reasons. An intrepid traveler, the author, whose real name was Jack Jones, had worked as an ambulance medic in Chungking in China from 1945 until his capture and release by the Communists in 1951, whereupon he found work with UNICEF in Bangkok (see my Chungking: China’s heart of darkness).

There he raised a large family with a Thai woman. After a stint in Jordan from 1959–67, they settled back in Thailand, where Jones died in 1984.

Bangkok has undergone numerous changes since the 1950s. The Klong Saen Saeb canal and the charming old city with the famous palaces and temples on the Chao Phraya River are still intact. The city’s confounding layout has no other convenient means of transportation to the old city than water taxis, which I rely on to get to and from Khao San and Sukhumvit to partake of the widest offering of massage parlors (of the legit variety). But there was little sex industry to speak of back then compared to today’s neighborhood upon neighborhood of red-light districts. The cult of sexual freedom propounded by the Andrianes was confined to elite circles. Not until the Vietnam War, and the expansion of the war to Laos in the 1970s, did Thailand begin to erect its notorious recreational industry, beginning with the Thai city of Udon Thani, fifty miles across the border from Vientiane, one of the early prostitution destinations catering to U.S. servicemen. Back in the 1950s, Bangkok’s nightlife wasn’t much more than a sleepier version of Hong Kong’s Wan Chai district, with a handful of sailor bars and brothels. It’s in one of these bars, the Bolero, that the hapless protagonist, Reginald Joyce, a young naïf posted to Bangkok by his British firm, becomes ensnared in a tortuous relationship with a prostitute named Vilay.

Reynolds has a knack for strategic focus, and the fateful setting when Reginald first meets Vilay, or “Wretch” for Reg as she calls him in her thick English, is sharply etched in odd, surreal details, which serve to adumbrate the subsequent story. The open-air bar is

like a share-cropper’s shanty on Brobdingnagian scale. A raised wooden floor, acres in extent; no walls; a low gloomy roof. From the gloom hang dozens of tawdry paper lanterns, all very dim and dusty. In the middle of the floor is a circular space waxed for dancing; this is flanked by the rows of tiny desks at which the girls sit like amazingly exotic schoolgirls in a kindergarten.

She had caught his eye on a previous visit, and he was back to see if he could make her acquaintance. She avoids him until he approaches her, then charges him by the hour to make conversation with him at his table. Ten minutes into the session, she affects boredom and indifference and gets up to go mingle with others in the bar. He forbids her to leave since he’s paying for her time. She then

leans far back in the armchair with her body almost supine and her head at right angles to it, propped up by the back of her chair. There is a frown on her low rather narrow forehead and her rather small eyes have gone smaller and are black with resentment. Her lips, tomato-red, are pushed forwards like a sulky child’s.

When she refuses to fill his beer glass, he himself gets upset and splashes the beer over the table and on her. She leaves his table again and returns. He pays for several more rounds of drinks. She makes him buy flowers from a flower lady, and when he’s not looking returns the flowers to the lady and pockets the money. She demands a bar fee to leave the bar with him and another fee to take him back to her flat.

There is no letup. The hard-sell tactics are repeated in anguished negotiations over the course of the entire narrative. The more entangled they become, the more refined her techniques of extracting money; the more he pays her, the fewer crumbs of affection she throws at him in return until yet more banknotes are peeled from his wallet. He only becomes the more obsessed, and soon he’s giving her most of his salary.

At first, we recognize the sheer callousness of a manipulative sex worker in the tradition of Zola’s Nana, but that alone doesn’t account for Vilay’s perverse behavior. Something else is going on. Their relationship has a more complex dynamic which seems to feed on itself. It’s almost as if his abject and revolting helplessness drives her to an uncharacteristic, sadistic extreme, if only to shock him into recognition. At one point her son is hit by a car and she refuses to go to the hospital to see him, in apparent denial over the gravity of the situation but also in sheer defiance of Reginald’s rectitude, who pays for everything and watches over the dying son himself. In another episode, Vilay convinces him to rob a family of his acquaintance, claiming she is greatly in need of a large sum of money, and he goes right ahead and attempts it. He is on the verge of physically assaulting one of the family members in their home when he is caught, but as it’s unclear what his intentions were, they desist from calling the police and let him go.

The ending of this study in psychological degradation, which I’ll refrain from spoiling, has got to be one of the most humiliating imaginable for a male protagonist at the hands of a sex worker—the sort of stark reversal or poetic justice that might even appeal to certain feminist readers. Others may find it an exasperating read, given how unbelievable it is that a man could so prostrate himself before a woman who excels in the art of treating him like a dog. I suspect that is indeed the point the author wished to make: such men are a dime a dozen.

Restaurant in Chiang Mai, Thailand, where Jack Reynolds’ novel is partly set.

* * *

More book reviews by Isham Cook:

Foreign devils on the loose in China: A review

Lotus: Updating the great Chinese socialist realist novel

The 1.3 billion-strong temper tantrum: Review of Arthur Meursault’s Party Members

The literature of paralysis: The China PC scene and the expat mag crowd

The ventriloquist’s dilemma: Asexual Anglo travelogues of China

Like this post? Buy the book (see contents). Now available on Amazon:

CONFUCIUS and OPIUM:

CHINA BOOK REVIEWS

Categories: China