CANNABIS SO CLOSE YOU CAN ALREADY SMELL IT

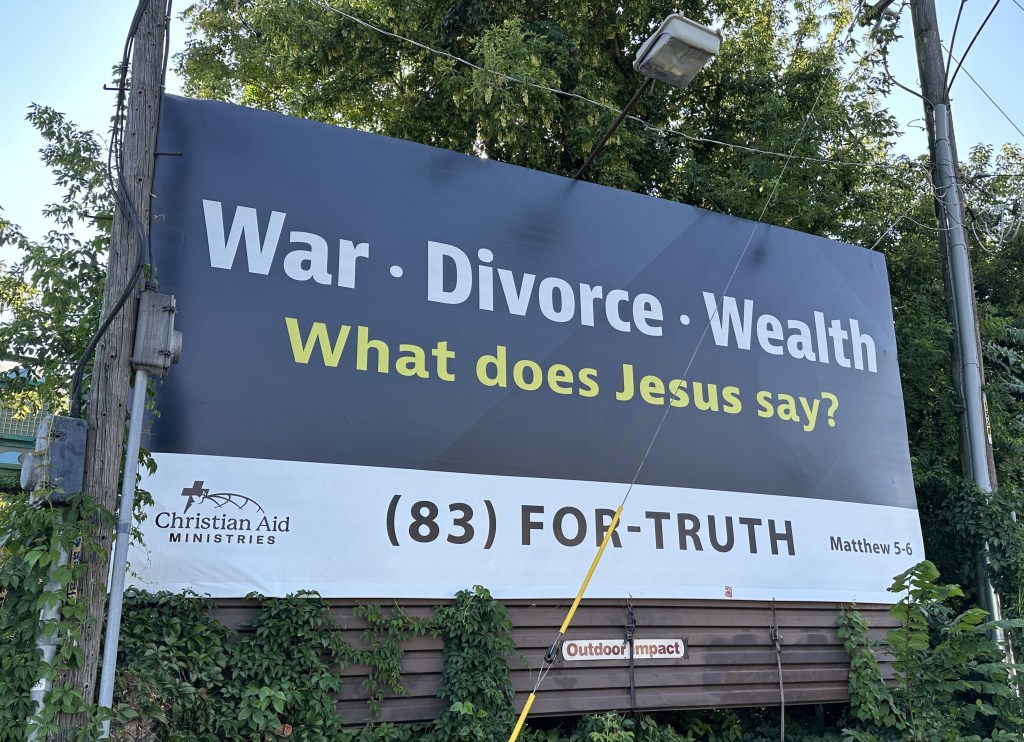

For reasons I am still trying to fathom, most of the highway billboards I see are for lawyers promising to extricate you from financial or medical disaster due to a drunk-driving conviction or an accident at the hands of a drunk driver. That there are people in such predicaments is not hard to grasp, and I understand the logic of placing these advertisements on the road where drivers can see them. But the majority of billboards? It must be a huge business, and it says a lot about the nature of entrepreneurship in the U.S., which profiteers so much off the economic hardship of the hoi polloi. Next in frequency are restaurant billboards, followed by Christian billboards, and a newcomer — cannabis billboards. Many of these billboards are goofy and entertaining. The Christian ones tend not to waste any words — “WHO IS JESUS?” with an arrow pointing to a Bible and the word “Matthew.” Or in simple block letters: “JESUS IS REAL.” In case you didn’t know. But others can be surprisingly witty. One in Michigan which enjoins us to “EAT. DRINK. REPENT,” with images of a beer mug and pizza under the heading “BEER CHURCH,” looked like it was paid for by The Onion. The billboard swooshed by too quickly to photograph, but I was able to find a more tepid approximation on the web which will have to do:

A plethora of cannabis billboards unfolded in Michigan where marijuana is legal — “ELEVATE YOUR HAPPINESS: ROYAL WEED” — but not so many in Illinois where it is also legal. There were even some in northern Wisconsin, where marijuana is illegal, as one approaches the Upper Michigan state line: “OUR CANNABIS IS SO CLOSE YOU CAN ALREADY SMELL IT.” I was impressed that Wisconsin billboard regulations allowed for the advertising of a product whose possession can get you thrown in jail for six months (three and a half years in the Pen for a second offense). This billboard also swooshed by too fast to capture, but I found a similar one on the web (left).

By the time we started realizing how memorable some of the billboards were, it was too late to go back and start over. You need to set out with the intention of “collecting” them. I’m not going to delve further into American billboard culture here, only to wonder why no one has yet come out with The Great Billboard Book. French philosopher Jean Baudrillard never mentioned the phenomenon in his 1986 road-trip study, America. Billboards do form an interesting plot device in the 2017 movie Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, by the British-Irish director Martin McDonagh (starring Frances McDormand). As with the 1984 road-trip classic Paris, Texas, by the German director Wim Wenders, it often takes a foreigner to understand the USA.

I don’t quite qualify as a foreigner per se, despite two thirds of a life lived abroad — Canada, Germany, Japan, and the last twenty years continuously in China — but I distinctly feel like one every time I go back home. This is not necessarily meant in a pejorative sense, just that it makes you notice things that domestics who never travel don’t. Covid-19 was a noteworthy rupture, forcing change everywhere. Before the present trip in the summer of 2023, just when the U.S. was getting over the virus nightmare and back to business, I had last visited the country during the blissful pre-pandemic era four years earlier, in spring of 2019, when most of the world had never even heard of the 1918 Spanish Flu.

Restaurants are a good entry point into the culture of the land. Entrees in modestly priced restaurants now run $17 at a minimum. For two people, throwing in a salad (also $17!) and two $7 pints of beer for good measure, plus the 6-8% sales tax and a 20% pre-tax server tip of $13, the bill comes to some $83. Thankfully, most restaurants don’t add on an irritating obligatory “service fee” (ranging from 5% to 25%), though this is apparently a trend, on top of which, they hope, you will tip the server the usual amount (or, they hope, you don’t notice the added service fee). Still, they have learned how to make you feel increasingly guilty about your tipping habits. I worked as a waiter in my younger days and am keenly aware of the need to tip the waitstaff, which they rely on to supplement their wretched hourly “tipped minimum wage” in many states of $2.13 per hour. But now the server’s handheld credit-card machine (likewise the cashier’s swivable iPad) only gives me a choice of 18%, 20%, 25%, or “Other.” Choosing “Other” allows you to type in any amount or to decline a tip, all in full view of the server. I would prefer not to have these figures thrust upon me like a multiple-choice quiz. I have also been conditioned by my decades in China, where like much of the rest of the world, restaurants collect neither tips nor tax; you simply pay the exact charge for the items you’ve ordered. Restaurant prices in China have also surged over the decades, and decent fare both domestic and Western now runs USD $40-$50 for two — still a deal compared to current U.S. prices (for more on Chinese restaurant culture see my Insights into China: A visit to a restaurant).

Many American restaurants seem dominated by the elderly, which makes sense if younger people are being priced out. But the latter are hardly priced out of bars and brewpubs. The other possibility is that tastes have changed. The younger generation still adores alcohol, but no longer steak and baked potatoes, or fried chicken and mashed; they tend more toward turkey wraps or vegan quesadillas. Beer prices have largely held steady since my last visit and the variety and quality are always excellent, though American visitors to the best Beijing and Shanghai brewpubs would encounter tough competition as the rest of the world learns how to make very good ales and IPAs. American cafe and coffeehouse culture remains vibrant, with however one big Covid-sparked letdown. The “great resignation” that took place during the pandemic — many not just demanding to work exclusively from home but quitting work altogether, especially lowly paid service work — has not fully rebounded. With coffeeshops thus finding it hard to recruit new servers and baristas, many shops only have a single eight-hour-shift worker. Since coffeeshops need to open at 7-8 am, they are thus forced to close at 2-3 pm. If you’re the beret-wearing type and rely on the cafe space for your daily work, as I do, you are now confined to the few shops, mainly Starbucks, that stay open later. The price of coffee has gone up as well, $3 a cup ($4 after tax and tip) and no free refills. I was warned by a few state-side friends that post-Covid America has become unfriendly and customer service nasty. This I did not find to be the case. Sunny baristas and servers remain one of the country’s more delightful points.

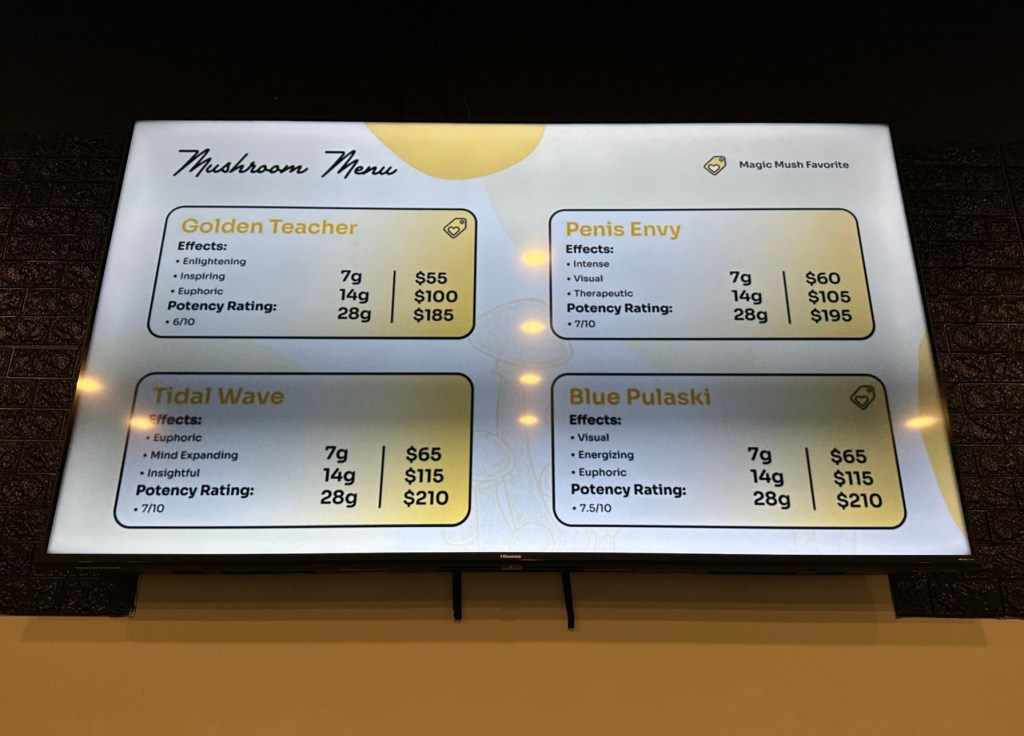

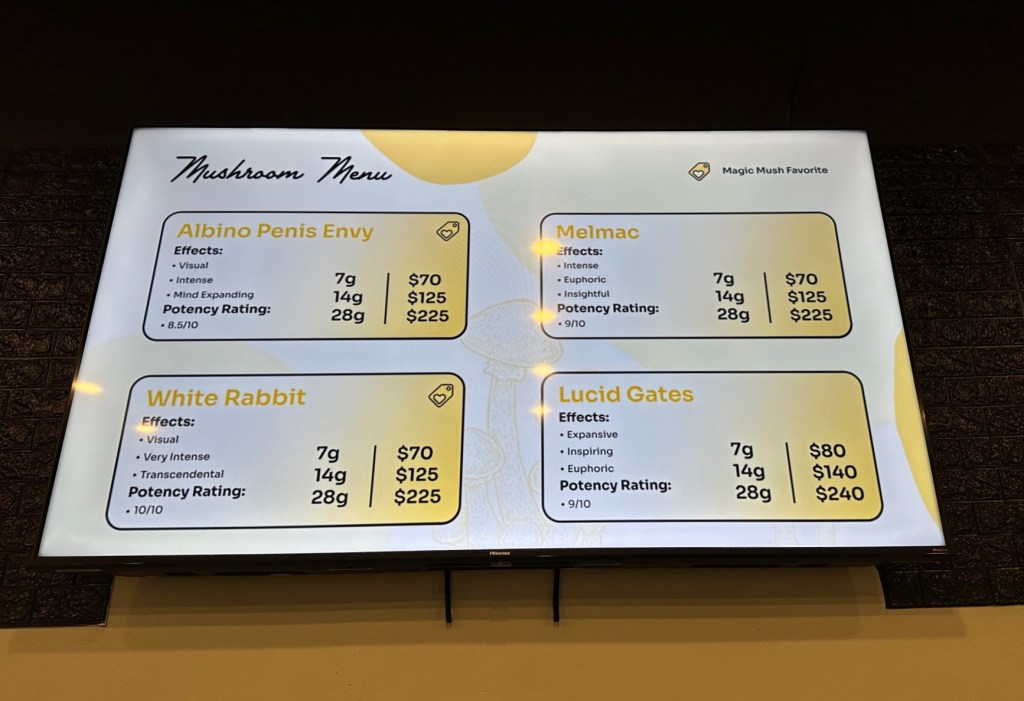

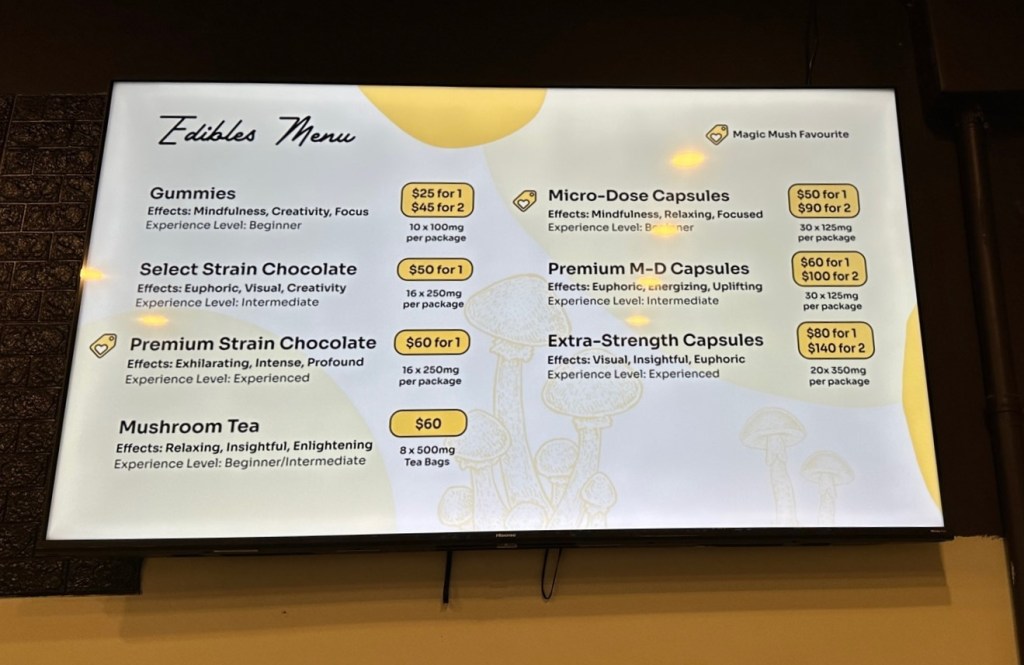

We are having pizza at downtown Chicago’s storied Pizzeria Due when I notice a bakery across the street with lettering on the window that says, “Sconed Chicago,” seemingly a pun on “stoned.” That’s odd, I thought. We enter the Wake N Bakery and sure enough, all the products, from edibles to coffee and teas, are infused with weed, apart from several “uninfused” items listed on a tiny placard. There are cannabis dispensaries all over the city now, but this is a first — a cannabis bakery cafe, with plentiful seating. The menu sign makes no explicit reference to “cannabis” or “marijuana.” There’s no need to, as it’s assumed everyone gets it. But for the benefit of any hypothetical customers willing to shell out $25 for a muffin who still remain clueless, there is a stylized cannabis leaf on the wall behind the counter. No conceivable person could fail to recognize this most universal of symbols, or not? Well, one fifth of the world’s population in fact. China has long been insulated from the most commonplace of popular referents, Mickey Mouse aside. When they think of drugs (dupin in Chinese = poisonous goods) what comes to mind is their national humiliation at the hands of the British imperialists, in other words opium. Or heroin or cocaine — it doesn’t matter what they’re called. They’re all just different terms for the same lethal substance. The more travel savvy may be aware that something called marijuana has been legalized in certain countries, and for the life of them they could never imagine why mainlining death is being legalized. They have only the haziest understanding of what this drug is. If they enter the Chinese word dama into their translator, “marijuana” pops up in English. “Cannabis” draws a blank and is not a known word, nor do they recognize the marijuana leaf symbol.

I can easily imagine some post-Covid Chinese tourists, who may soon be returning to the U.S. in droves, strolling into such a shop and, having no idea how much a muffin should cost, munching one down with a latte. In case you don’t know how strong edibles can be, my wife and I shared a single muffin in Amsterdam once and got lost trying to find our way back to our Airbnb. Jack, a friend and neighbor in rural Michigan where we own a cottage, grows his own and recently whipped up some “cannabutter,” which he uses to help him get to sleep at night. He warned me it was strong. I spread a tiny dab on the corner of a piece of toast. Another friend who had driven up from Madison joined us; Bill and I had attended the University of Chicago together in the 1980s. Chen, my Chinese wife, was still processing an intense encounter with magic mushrooms the previous week (more on which later), and to be on the safe side I didn’t give her any.

Edibles come on slowly and it took two hours before we felt buzzed, though when I asked him, Bill still said he wasn’t sure. We were to head out to dinner later, and to kill time I sat back on the sofa and drifted off into a reverie. If nothing else, the buzz was sparking creative thoughts. Then, feeling restless, I got up to take a walk down the country road and now realized how massively stoned I was. After what seemed a good half hour of brisk walking, I passed by the old school bus sitting in the yard of a neighbor. It actually takes only five minutes to reach that bus on foot. As time slowed down, my mind was racing. For the next five hours I was strung out on a rack of extreme self-consciousness and inadequacy, so much so that I had difficulty forming coherent sentences. When Jack drove us to the restaurant, I recognized none of the roads or had any idea how we got there. I didn’t tell Chen how high I was because I didn’t want her to worry. Delicious as the meal and the carrot cake dessert with freshly whipped cream was, I had no appetite. Only later back at the cottage when we had fired up the hot tub did the drug start to release its grip on me. Bill agreed that he got “too high for comfort.” Cannabis is a divine drug and medicine when used wisely, but the poor tourists who don’t even know they’re about to be slammed by Tetrahydrocannabinol terror, when all they did was eat a muffin, might find themselves checking into the emergency room thinking they’ve been poisoned. I would hope, therefore, that the shop has the good sense to warn any customers who appear slightly confused about where they are.

TWERKING, JUMPING AND STOMPING ON CARS

My last Chicago Pride Parade was exactly thirty years earlier, in June 1993, and it was quite a scene at the time, with big bold floats and brash displays of sexual bravado. The June 25, 2023 parade, by contrast, went on and on…and on. We didn’t stay till the end because frankly speaking it was a bore. The pride parades have become so commercialized that there is only room now for the staidest of LGBT-sponsoring businesses — the Chicago teachers union, the fire department, the public library, and just about every bank in the city. None of these organizations can afford to seem anything less than strictly normal. I suppose it’s a good thing if you’re gay to have this backing of the whole society.

Meanwhile, the action is happening elsewhere, only a few blocks over on Belmont Avenue, where hundreds of skimpily dressed, mostly black women are “twerking” — sexually humping the ground — to loud dance beats. They gather in circles right on the street and try to out-bump and out-grind each other. Some are topless with painted nipples or are letting their breasts hang out through holes cut in their shirt. It seems to have been spontaneously organized. The police have blocked off the street in front of the Belmont El stop (elevated railway) and allow them take over several blocks just west of the station. While there are twerkers holding gay pride flags, they are clearly finding this street theater more fun than the pride parade going on nearby. It was inevitable, I suppose, that a more brazen form of entertainment would arrive to shake up pride parade fatigue, and here it is. If this Pride Day twerking is a recent phenomenon (some noted it had started happening only the year before), it is already getting out of hand. They continued to assemble for several more days and evenings, and it came out in the news that a number of parked cars had been damaged after being stomped upon. One witness “saw some groups getting in heated arguments, someone getting arrested, a girl bleeding and screaming, then the jumping on cars….Felt like the vibe could have changed quickly if something ticked someone off which made us all walk faster/try to find alt routes away.”

A more alarming form of street theater is the increasingly organized flash mob: hundreds of teens assembling by cellphone command to “smash and grab” shops and wreak general havoc. Downtown Chicago was spooked by one last spring that resulted in gun shots and innocent bystanders being accosted. Covid saw an upsurge of crime around the country. Statistically speaking, your chances of being killed in a random robbery or assault was significantly higher in the 1970s than today, but that’s not very reassuring with so much gun violence and mass shootings in the news. It’s paradoxical. On the one hand, if you have lived in the U.S. your whole life, you’ve acclimatized to the specter. You have to push it out of your mind or you’d go crazy with paranoia. If everyone you see seems relaxed, as if the problem doesn’t exist, it’s because people must get on with their lives. And you and your family will in all probability get through life without too many threatening encounters.

On the other hand, Americans have little understanding of how appalling their country appears to outsiders. I’ve worked with foreigners in the education field in China for decades. Many have never been to the U.S. and you couldn’t pay them to go there. Canadians are a bit more familiar with the States but Brits, Aussies and Kiwis are typically repelled by the country, especially in recent years with the gun fetish all over the media. The fact that there are millions around the world trying to flee to the U.S. and other developed countries from worse circumstances does not invalidate this. If you spend any time abroad, you’ll discover that most people (the impoverished excepted) have about as much interest in the greatest country in the world as they have in Saudi Arabia.

While again, statistically, your chances of being a crime victim are low, the violence is real and ever present. The Chicago neighborhood where we stayed exemplifies these contradictions. Our friend and host, who comes originally from India, lives in the western portion of East Rogers Park (as opposed to the marginally safer West Rogers Park), along Chicago’s northern border with Evanston. He’s been living there for almost two decades without incident. Rogers Park also borders Lake Michigan, and the narrow stretch of community between the lake and Sheridan Road is also reasonably safe, that is, as prone to crime as your average city neighborhood but not egregiously so. On the other side of Sheridan Road extending several blocks to the Howard El stop, things get dicey. A white male student from nearby Loyola University was randomly shot in the leg walking in a park there during our very stay that summer. “It’s disgusting,” angrily remarked another friend on this incident, a female Northwestern University professor who lives in the area and is comfortable enough walking around during the day but relies on Uber at night.

Later in the summer on our road trip to the East Coast, we met up with a couple I’ve known from my college days, Sue and John, who used to live in East Rogers Park and now live in Germantown in Philadelphia. She’s a college teacher and he’s a carpenter; they live on a modest salary and own their house. I had them recommend a hotel nearby we could stay in. They suggested one in the upscale Chestnut Hill community a couple miles to the north. Though swinging by to pick them up for our dinner date shouldn’t be a problem, “I can’t emphasize enough how much gun violence there is in our neighborhood,” Sue said. John had served in the army and could identify from the direction of the gunshots they routinely heard whether they came from gangs settling scores or random robberies. I asked them to compare Germantown with Chicago’s Rogers Park, where they had also been accustomed to the sound of gunfire. They had to consider that for a minute before deciding the two neighborhoods were equally bad. At the same time, there is enough of a sense of community — neighbors looking out for each other — to keep them there.

One solution to community violence is more robust social services. The side entrance to the Howard station in Rogers Park normally sees a gaggle of pot-smoking black men standing around. Though they generally keep to themselves, to many, they might look suspicious or intimidating. One day they are gone — something must have led the police to banish them from the entrance. Not far away on Clark Street and Rogers Avenue there’s a liquor shop where we saw a drunk black woman half dancing, half staggering outside with her shirt open and breasts exposed. At the same corner a drunk Mexican man managed to wedge himself in a bus stop bench railing and had to be untangled by the fire department. Another day witnesses something we were to see more than once: an angry black man flailing in the air and yelling and cursing explosively. In Dupont Circle in DC as well, a black man screamed at a black woman nearby to get away from him; it was unclear whether she had provoked him or he had lashed out at random. If you’re walking down the street and find yourself face to face with a frantic person who looks like he’s about to land you with a punch, the likelihood is he won’t. At least blowing off steam by visibly acting out is preferable to quietly preparing to rob or shoot people. It could even be called a kind of performance art, if a perverse one: they may not be looking at you but want you to witness their agony nonetheless, and this may have a certain therapeutic benefit. Many of them have been turned out of mental institutions that ran out of funds. They may not even have money for medication. Some homeless ride the subway all day as there is air conditioning and heating, or they have nothing else to do. During a 2018 visit, I recall a white man on the Chicago El yelling and crying that he was losing his mind because he didn’t have his meds.

A charming feature of Americans is their penchant for starting up conversations with strangers on the street, in elevators, on buses and the subway. Though cities can vary and we didn’t see much talking on the Boston and DC metros, the Chicago subway is another matter, with a scene almost always going on in one car or another. And unless I have only now begun to notice it, there seems to be an upsurge in El train drama over the past decade. Heading north on the Red Line from downtown one busy weekend evening, the train is crowded and we have to stand. We are both wearing straw sun hats, and a black man who has been jabbering away to anyone who will listen asks us if we are from Las Vegas. Two passengers sitting next to him on the bench get up to leave and we take their place. The man is drunk but we humor him — until he drops his cup of beer and it spreads on the floor. “Now you straighten up and stop making trouble for folks,” a black woman admonishes. Everyone takes it in stride with smirks and smiles as we move out of the way.

From the El stop, walking through Pottawattomie Park to get to our friend’s place feels reasonably safe in the summer evening at dusk. On weekends especially, the park is filled with kids playing baseball and picnicking families, mostly Mexicans but increasingly Somalians, Ethiopians, and Middle-Easterners, including women in niqaabs. It’s a very ethnically mixed community. This is another solution to neighborhood violence, one so obvious it barely needs repeating: when enough people are out and about at all times of the day and night, bad elements go into hiding. It’s when fear of violence drives the majority into hiding that the demons come out of the woodwork.

Nothing illustrates this better than the two Tennessee cities of Memphis and Nashville. Both have similar city populations, though Nashville’s metro population of two million is about a third larger than that of Memphis. Both are famous for their music, indeed could be said to represent the two main historical strands of American popular music — country music and the blues, white music and black music. Each has a downtown street where the music scene is concentrated, Beale Street in Memphis, where black musicians flourished after migrating from New Orleans, and Broadway in Nashville, where country musicians cut their teeth.

There the similarities end. Nashville is vibrant and exciting and jampacked with people, including guitar-toting musicians looking for gigs, prowling the endless bars where live music is going on practically around the clock. The city is clean and feels safe and well run. Despite the white bigot we passed by who snarled at Chen something about “your fucking white boyfriend,” the crowds evinced a mixture of ethnicities, less white than I had expected. By contrast, walking from our hotel the half-mile to Beale Street along Memphis’ Main Street with its showcase antique-style streetcars feels like a ghost town. There are few people out, at daytime or evening, weekends or weekdays. At both ends of Beale Street and at each cross-street police cars are parked to reassure tourists they’re safe on this forlorn strip of history. Since we were visiting some of the cities on our trip for the first time, I looked up online crime maps beforehand to get a measure of which neighborhoods to avoid. Most cities, including Memphis, show downtown neighborhoods awash in almost daily homicides. In 2023, Memphis ranked as the most lethal U.S. city with 63.9 murders per 100,000 people, whereas Nashville had a more reassuring 14.4. More reassuring still was Toronto, with 2.6, where we were headed via western New York State, to visit a friend we had known in China and was now back home and retired. (For more context, the homicide rate for all of China in 2020 was 0.5.)

THREE-DIMENSIONAL CHRYSANTHEMUMS AND A CANADIAN DETOUR

Besides being able to wander stress free in a major North American metropolis without being harried by the thought of guns, I had another goal in Toronto, this most progressive of cities, something I’d never imagined being able to do in my lifetime: to legally buy magic mushrooms (psilocybin) in a dedicated shop and consume them at an officially sanctioned nudist beach. The closest you can get to accomplishing this in the U.S. is purchasing mushroom-infused chocolate bars over the counter semi-legally (illegally claim the police) at one of Oakland’s smoke shops, where the consumption but not the sale of psilocybin was decriminalized in 2019. Then head over to San Francisco’s clothing-optional Baker Beach in the shadow of Golden Gate Bridge (I’m not aware of any convenient options to combine both activities on the East Coast). Two fundamental freedoms which should be universal: 1) the freedom to consume the drugs of one’s choice whether medically or recreationally (not to mention the freedom to grow and consume any and all flora — is there anything more absurd and outrageous than the outlawing of plants?). 2) The freedom to go naked, not just in the privacy of one’s home (many can’t even bring themselves to do that) but in mature social and public settings. We shouldn’t forget two more that Canada provides: 3) freedom from both gun violence and the perpetual threat of violence. And with their nationalized health care, 4) freedom from financial disaster (likewise the worry of financial disaster) due to a medical emergency or grave illness. (See my The sewage system, or What is fascism? on the cost of paying for a gunshot wound in the U.S. — providing you survive it — should you lack health insurance.) Finally, dog owners in Toronto enjoy a fifth freedom: landlords may not prohibit tenants with pets, and leashed dogs are allowed on public transportation (buses, the subway, commuter trains).

But to backtrack a bit. Chen and I first tried mushrooms on our last trip to the U.S. in 2019, at our aforementioned Michigan cottage; a friend put me in touch with someone selling dried Psilocybe cubensis by the ounce. I myself had considerable experience with LSD and mescaline in my teens but hadn’t touched either in the years since due to several bad acid trips. Chen’s only previous experience with a hallucinogen was weed. I picked out two of the larger mushrooms in the jar, which together weighed a bit over three grams on my digital scale, and we each ate one — supposedly a fairly modest dose. It took a while to get off, so we boosted it with a little pot. Soon I had the sensation of looking out through a circumscribed field of vision, as if from a visor or helmet. Chen is a graphic designer and Photoshop expert and she noticed that everything around her was missing the M (magenta) from the CMYK color scheme, rendering the sky a pale turquoise, yet all was lit up as if from backlighting. We both saw the walls and carpet gently shifting and undulating. Later she started crying and didn’t know why. I had warned her there’s an iron rule with psychedelics: you can’t fight it. It will fight you back like your reflection in a mirror. You have no choice but to go with the flow and let it do its thing. Then she was fine, we came down and that was it.

For our second experience together, not long after arriving in Chicago on our 2023 trip, we each took two small mushrooms for an art museum visit — something I’d always wanted to try. I have a theory I’ve written about elsewhere that I call the “museum paradox.” For people who view the world aesthetically, as I do, everything is artistic. Women can’t understand why men insist on staring at them. Rude staring is of course annoying. I stare as politely as I can, just momentary glancing. It’s not to harass or even necessarily to indicate my desire. Rather, I am magnetized to an object of beauty that happens to come into view; it could apply equally to male beauty. Women who visit art museums tend to be on the cultured side, with good taste in dress, and not a few are very attractive. Paintings merely pose or masquerade as real, or even as ideal — more than real. But to my jaded self, having visited as many art museums and read as many art books as I have, they simply can’t compete with the real thing: the object of beauty standing right there next to me, viewing the same painting I am viewing. This is the strange paradox, that I am drawn more toward a living object of beauty than a painting. Could it really be that the most interesting thing about museums is the people who go to them?

I reckoned that mushrooms might “reset” the situation and refocus my attention on the paintings. That is exactly what they did. It was the same stash, which I had kept in my friend’s freezer, and I worried it would no longer be fresh after four years. Not only was it still fresh, I got higher than ever. Chen and I both saw the paintings breathing and bristling in transparent 3D. I was particularly taken with Renoir’s “Chrysanthemums,” so alive I could smell them. Every painting became highly charged. Just walking into a new room of paintings was dramatic. It was perhaps the perfect “museum dose.” (For a systematic treatment of the possibilities combining various psychedelics with art museums and live music, see Daniel Tumbleweed’s The Museum Dose: 12 Experiments in Pharmacologically Mediated Aesthetics.) A stronger dose and the experience would have become overwhelming; I might have had to leave the museum to get a hold on things. There would be simply too much going on, too much emotional material being splattered about by artists who after all worked with emotion (as opposed to paint) as their primary material.

Marijuana also provides for a fruitful museum experience (that I have also tried), but there is a stark difference compared to the stronger hallucinogens. Weed works quantitatively and is rather predictable: the more you take, the more you get of the same. If you enjoy food, it’s more delicious on weed. Norman Mailer once remarked that sex is never quite as good without weed as it is with weed. If it makes you confused, taking more makes you more confused. Take too much weed, and it just makes you sick. The psychedelics, on the other hand, work qualitatively. We’re dealing with something considerably more potent, and you can feel this potential even at lower doses. On low doses, both marijuana and mushrooms lend a certain silliness to museum art; more marijuana might turn a painting profoundly sad or tragic, but all would be safely contained within its frame. With mushrooms, you sense a high-voltage energy under the surface that is on the verge of leaping out. On a very strong or so-called “heroic” dose (the term comes from Terence McKenna, the most eloquent of psychonauts), there’s no telling how it might impact things. At a certain point, the museum would fragment and fall apart as hyperspace takes over and reality gives way like melting cheese.

Toronto has several shops selling psilocybin and we found one in Chinatown. The drug presently lies in a provisional “hands-off” gray area, allowing the government to pilot recreational sales in preparation for potential legalization, the same process cannabis went through; if problems start arising and too many people wind up in emergency rooms, they can shut it all down. When I asked the staff in the House of Mush whether the drug was legal or illegal, the answer was “legal.” Their menu offered a variety of mushrooms and edibles. I decided to go for the “Intermediate” level “Select Strain Chocolate,” infused with four grams of mushrooms in sixteen pieces: six for me, five for Chen and five for Anne, our Canadian friend. That meant 1.3 grams for them and 1.4 grams for myself, about what we had taken in 2019. The elf-like young hippie at the counter cautioned us in oddly articulate tones, as if having to repeat the same for a steady stream of naive customers, that chocolate shrooms come on faster and you are aware of the importance of set and setting? There is a funny YouTube video I only saw after the fact, “Adam Eats an Entire Mushroom Chocolate Bar,” in which the creator, “AdamIsPsyched,” well versed in mushrooms in their natural state, consumes a three-gram chocolate bar for the first time (i.e. twice as much as we each had). Seven hours later he emphatically proclaims, “the chocolates are a lie.” They were actually the equivalent of five to seven grams of regular shrooms. It was the strongest mushroom experience of his life, so strong he felt himself thrust into DMT territory and witnessed his personality “splitting into fractals of itself.” Indeed, I found on the internet that chocolate is a natural MAOI (monoamine oxidase inhibitor), which boosts the effects of psilocybin (as ayahuasca does with DMT).

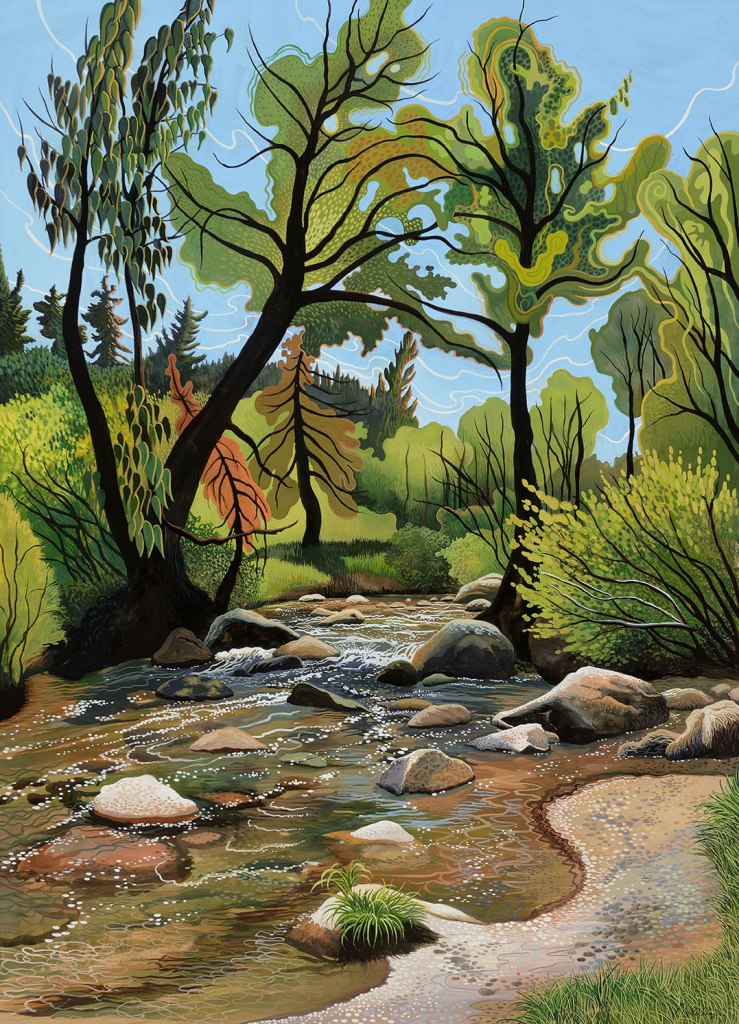

Hanlan’s Point clothing-optional beach occupies one side of Toronto Islands, facing the Mississauga skyline to the southwest rather than the Toronto skyline on the other side. After arriving by ferry at noon, we find a snack stand on the way to the beach. Having eaten the chocolates on an empty stomach before washing down soggy ham-and-cheese wraps with beer, they come on strong indeed, starting to hit after only twenty minutes, while we are still at lunch. I feel a pressure in my head like the throb of a headache and a wave of dizziness that almost knocks me out of my seat. We head for the beach. The dizziness is gone, and I am now in a storyland. Everything looks cartoony (like the picture at left), the trees sprouting hands and halos and waving, animated and human-like. Perhaps the wind is doing this but it isn’t windy. We follow Anne, who seems to know where the beach is though she hasn’t been there before. She reveals that she has only taken three chocolate pieces: “I know myself.” I ask Chen how she’s feeling. “I’m not sure,” she says. As for myself, Oh boy, here we go. Go with the flow.

At the beach, the nudity is only an afterthought, as the psilocybin takes center stage. On our left lies an attractive Asian Canadian wearing a bikini bottom and her naked white boyfriend. On our right, a trio of fully clothed young Japanese women, drawn to the beach but stopping short of doffing their clothes. There is a curious parallel between getting naked in public and trying a psychedelic drug for the first time. For many people they may be equally terrifying for the same reason: you have to surmount deep ideological conditioning. Not to mention in few countries can either be engaged in legally. That they made it to the beach at all is impressive; don’t laugh at us, give us time and we’ll get there, they seem to be saying. I’m tempted to tell them point blank that after your first time it’s easy. But they need to figure out how to cross the “crazy” line on their own, which once crossed is not craziness, they’ll realize, but freedom, a conceptual freedom far more valuable than any external freedoms allowed by society (we’re not advocating a free-for-all here; I don’t support mother-son marriage). Chen and I get naked. Anne’s clothes come off later.

Meanwhile, the rows of sand before me are scrunched up accordion-style; the sand appears as some alien plastic substance. I touch Chen’s back and it feels like it’s covered with an invisible layer of cotton. The Mississauga skyscrapers in the distance are turning into people, bending and dancing into Lake Ontario. An Aztec-like mask forms across the sky, transparent but unmistakable. I close my eyes and brilliantly burnished metallic orbs spin by on rollercoaster carousels. I am then caught in the turning shards of a kaleidoscope, an awful and majestic ego-grinding machine, which I feel I am mysteriously undergoing for my benefit (I know I am only being given a taste and a higher dose is needed to be ground to bits). Someone nearby is playing music on their phone and the music itself forms the gears of the kaleidoscope, tinkling like a music box.

“Oh my god,” Chen mutters. She is preoccupied with her hands or the sand or something. Soon she is crying. She says her head feels blown up like a balloon and she can’t feel her face, and we appear to her very far away. She is confronting herself in the funhouse distorting mirror and starts panicking and hyperventilating. I embrace her standing up and tell her to take deep slow breaths. “It will pass. Be patient, it will absolutely pass.” People are staring. “Is she okay?” the topless woman next to us asks. Chen is starting to make me panic and I ask Anne if we should summon emergency services. “No!” Chen says, getting a grip on herself. It’s her last and biggest wave of anxiety and she starts to calm down. Soon she’s fine. We stroll naked hand in hand along the beach.

Toronto Islands is really a big botanical garden, and the greenery, foliage and flowers are resplendent on the way back to the ferry. I’m exhausted from the shrooms and feel “split” as I try to integrate the experience. This feeling persists the next morning. Chen is back to herself. We visit the Distillery District with its cafes and art galleries and by the afternoon I feel much better. The mushrooms definitely worked some magic. For the next several weeks, I am enveloped in a glow, an extraordinary sensation of clarity. The air smells fresher, colors are richer, sounds more intricate. I am more attendant to the surrounding environment and everything is a tad more interesting. I am reinvigorated with a feeling of patience and friendliness toward people.

SCENES FROM THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AMERICAN FAMILY

We leave Canada for our next stop, a Japanese friend in Kalamazoo, Michigan, which we reach after a six-hour drive via the Port Huron crossing. A widow (her American husband died six years ago), Sakura lives with her seventeen-year-old daughter and eighteen-year-old son. We meet the daughter briefly as she is heading off to a summer restaurant job; she is cheerful and courteous. We don’t get to meet her son. Immersed in his video games, he won’t emerge from his bedroom during our three-day stay. More evidence of a pattern I’ve begun to notice.

Bill, the aforementioned Madison friend who got baked with me on the cannabutter, had himself married a Japanese woman. They had a son together who in his later teens, for fraught, enigmatic reasons, became estranged from him. After decades together they divorced, she went back to Japan and their son followed, where he now lives quite contentedly, it turns out. Then there is Wei, a former Chinese student of mine when I was teaching in Beijing in the 1990s, who married an American jazz musician after immigrating to the U.S. It seems he had a volatile temper, and they divorced some years ago. She got custody of their daughter and found a man more suited to her, Mike, who worked for the Army Corps of Engineers. Wei and Mike are a model couple, liberal in outlook (nudists, hot tubbers) and as sane, loving and responsible as you can get. The daughter had never seemed greatly affected by the divorce until recently, when she began having anxiety attacks, apparently sparked by conflicting, tormented feelings toward her biological father (a constant taskmaster she could never satisfy) to the point where it has affected her own sense of gender. Now fifteen and in high school, she dresses in boys’ clothes, insists everyone call her “Charlie,” and wants to have a sex change.

I am not suggesting that mixed-race children of Asian-Caucasian couples are doomed to having identity issues or psychological problems. And I am certainly not advocating against intermarriage. On the contrary, the more the better: there is no more effective way to combat racism. Another old pal we visited, Alex, a Chilean American I went to college with, had met a Japanese woman, Sato, in an art museum in DC. He followed her to Japan and married her. They later wound up back in the U.S. and have been living in a big old house in a DC suburb with their twenty-year-old daughter. Aya is trilingual in English, Spanish and Japanese and is mature beyond her years. While Alex shows me the tomato plants that he’s trying to protect from the deer who break into his garden, before we head up to see his Buddhist literature collection in his sunny attic library, Aya prepares Chilean-style empanadas and sits with us out in the backyard gazebo, curious and interested in our conversation. It must be Alex’s Buddhism, combined with Sato’s dignified presence, that has rubbed off on Aya, as I don’t think I have ever met such a young woman as calm, centered and gracious as her, a solid exception to the pattern.

Passing through New York state on our way to Canada, we stopped in Ithaca to visit another friend, Peter, who lives with his Chinese wife and their fifteen-year-old son. They are another lovely and loving mixed-race couple. Peter is a retired English teacher (we met in China). His down-to-earth wife from rural northeast China, Rose, works in a restaurant at Cornell University. You would never expect they’d have any challenges raising a child, but the pattern crops up again. Though their son attends a good high school and gets straight A’s, he never leaves his room. He’s also addicted to video games, but I’m not sure that explains the problem. It could be that video-game addiction is not the cause but the effect of a deeper malaise. Virtual reality is our modern form of opium, seducing not just youth but everyone. Teens, however, are far more susceptible, especially if they never develop social skills to begin with. If they’re of mixed race, they may be victimized at school, whether worn down by micro-aggressions or outright racist behavior, in any case never fitting in, which only compounds these difficulties, deepening their isolation and their addiction to electronic opium, a vicious circle. At least Sakura’s son, who is in a similar predicament, is heading off to college where he will have to break out of his shell and gain rudimentary social skills.

I met Sakura decades ago in Osaka while teaching in Japan and tutoring English in an insurance firm where she worked. She followed me to the U.S. where I was embarking on graduate study and lived with me for a time until going our separate ways. I was returning to China and she prepared for graduate study at Indiana University, where she met Ralph, a junior. They soon got married; she was in her late twenties by then and he was twenty-one. I met him once on a trip back to the States. He was standoffish, keeping his arm protectively around Sakura the entire time, as if I was about to try to grab her away, when I only hoped the best for them. Although he earned a PhD in entomology — the study of insects — he later found his calling as a photographer. They moved around before settling in Kalamazoo. All I knew about him thereafter was that he kept pet reptiles. I remained in touch with Sakura on Facebook and some years ago she said she was going through a difficult period with Ralph and feeling depressed. She wouldn’t go into detail except to say he was inviting several women to live with them. It was not till I saw her again after all these years that I got the whole story.

Ralph had the meticulous attention to detail required of both the entomologist and the photographer. The butterfly display at left gives an idea of how the entomologist’s mind works. Another interest of his was polyamory: collecting women for concurrent, open and consensual sexual relationships. In this it helped that he happened to be exceedingly handsome and charming. You could say his assets and talents combined to enable him to develop his full potential as an artist. In Ralph I saw something of myself, in the way he viewed the world through aesthetic lens, and it wasn’t difficult for me to comprehend what transpired next. Instead of a two-dimensional display case, he mounted his collection in a three-dimensional space: the extra rooms in his home.

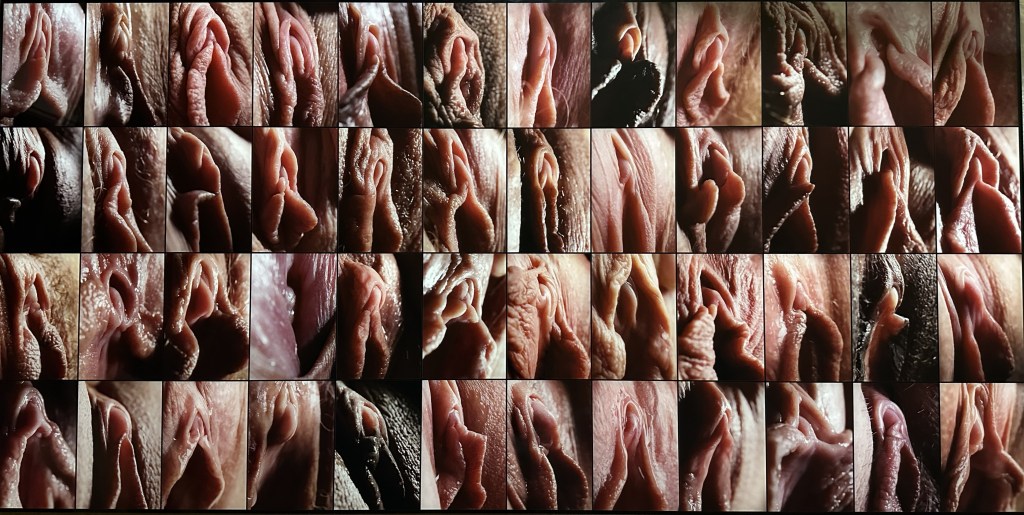

Their property had a large coach house, with furnished apartments on two floors. In them he installed two of his lovers, though they turned out not to get along and eventually moved out. He then set up a photo studio in the coach house and began to amass a collection of highly accomplished erotic photography. One masterpiece featured forty-eight vulvas exquisitely mounted on a huge glass plate (displayed below with permission). I asked Sakura how he managed to persuade so many women to have their genitals photographed. Well, she said, you can’t exactly identify who they are from their genitals (though I suspect Ralph could), but all signed consent forms. Some were professional models, others friends and lovers in his polyamory network. Ralph had sold some of his works at Detroit’s annual erotic art “Dirty Show.” When everything fell through, Sakura was left with his remaining artwork she now doesn’t know what to do with.

She stressed that Ralph wasn’t an old-school polygamist but an honest polyamorist; he allowed and encouraged her to find male lovers of her own. It was not something, however, she felt inclined to do. His own relationships were, in her words, “wide-ranging”: “friends, girlfriends sleeping with him sometimes, and partners who were more committed.” In polyspeak, Sakura was his “primary” and the others his “secondaries,” but Ralph had his own hierarchy: his “partners” (Sakura and the two housemates), his “lovers,” and his “girlfriends.”

To his dismay, he found himself developing erectile dysfunction problems. I can speak from experience about this and could have given him some advice. He was not going impotent, as he feared; he was merely experiencing penile exhaustion. The solution is to stop fucking for a month or two and it bounces right back. Instead, he started taking Viagra. His family also had a history of heart disease. One day he was with a newcomer to his circle, a young lass in her early twenties. One of the women who had formerly been living in the coach house let Ralph and the new girl use her apartment while she was out. He felt a pain in his chest, serious enough that the girl quickly got him into his clothes and rushed him to the hospital. He was having a massive heart attack. Sakura found out a few hours after his admission when the police came to her door (the girl was too busy getting Ralph to the hospital to phone her). He was already in a coma when she arrived, and she never got to speak to him before he died. He was thirty-eight.

You might regard this story as tragic. Of course, any life cut short before its time is tragic. But it would be wrong to blame his lifestyle as “tragic.” I myself identify as a polyamorist and wish I had gotten to know Ralph. We are all constrained by our various circumstances. Some are graced with the opportunities to venture further along an experimental lifestyle than others. Sakura emphasized to me that she does not regard herself as a “victim” and remains close friends with several of the women involved with them. Now devoted to her kids and giving them a semblance of normality after the chaotic years, she has not gotten back involved in the polyamory scene in the years since Ralph’s death. Once they’re both off to college, the world’s open to her.

* * *

Related posts by Isham Cook:

American rococo

American massage

An American talisman

The state of rage: The American sexual dystopia

The sewage system, or What is fascism?

Sexual Fascism: Essays

Also of interest by Isham Cook:

THE TAO OF POISON

“The bold characters, kinetic plot, and rich sense of atmosphere make this epic tale a studied contemplation of how beauty can usher in tragedy and sorrow.” — BookLife Reviews by Publishers Weekly

Leave a comment