For me, coffee is very special; its aphrodisiac effect has a concrete impact on life. Firstly, it determines my geographical living environment; secondly, it determines my psychological creative environment.

Zhou Xiaofeng, Preface to Yu Zemin’s Looking at Europe from a Café

If you’re wondering why I’m writing about cafés instead of teahouses, the answer is simple. The retail coffee business in China is a much bigger deal these days than its indigenous counterpart (though I will be touching on teahouses later as they’re part of the story). Shanghai alone has around 10,000 coffeehouses, more than any other city in the world and considerably more than its 3,000 teahouses[1]. Per capita, Shanghai is topped by the hippest city in China you’ve never heard of, Guiyang in southwest Guizhou Province, with one coffeehouse for every 2,000 people, versus 3,000 in Shanghai (Ou, Wu & Ni). These are just two of the nation’s cities partaking of the coffee renaissance.

How things evolved from coffee’s origins in Shanghai a century ago and earlier, going back to the 1860s when China opened to Western immigration, is a story that would require a book. In fact, in recent years interest among Chinese writers and researchers in reconstructing the lost Shanghai of the 1920s-40s has burgeoned, providing a wealth of new information. Let’s briefly recount some of the highlights of old Shanghai coffee and café culture before moving on to my main purpose here, which is to trace this culture back as far I can from my own experiences and encounters[2].

The “Paris of the East,” as old Shanghai was known, has been extensively documented in literature, film, and photography. In present-day Shanghai, many of the original buildings of the era survive intact, carefully preserved by zoning laws and wealthy patronage, and there are plenty of walking tours conducted by history enthusiasts. Nevertheless, it is difficult to convey how much has vanished. Coffee was absolutely central to Shanghai life. If it wasn’t for the cultural devastation of the post-Liberation years (1949-76), when for a generation virtually all of the city’s entertainment venues were forced to convert into proletarian eateries or shutter for good, many former cafés would still be around, as in Paris and Vienna today. We know about the names, ownership, and locations of the city’s former cafés; we are gradually, painstakingly, reimagining the rest, enough to visualize and relive them from within.

The first establishments where coffee was served were the bars and restaurants opened by westerners for westerners in the nineteenth century’s latter decades in the International Settlement (jointly governed by Britain and the U.S.) and the French Concession (Chen, Study). At the turn of the twentieth, two separate worlds remained: on the one hand, Chinese locals living in the claustrophobic walled city squeezed between the French Concession and the Huangpu River (the wall was torn down in 1912), along with the locals who had been migrating to the concessions, the men with their tea and tobacco water pipes and their women cooped up in their new homes (the lively courtesan and prostitute communities excepted). On the other, the western elite, whose cafés operated out of the lobbies of the concession hotels (a development recapitulated in the 1980s-90s, when the coffee industry again had to start from scratch and the only places serving coffee were five-star hotel lobbies, to which, as in the former era, locals were often denied entrance). The division was as much psychological as political—the Chinese could no more stomach the “cough medicine” known as coffee as racist westerners could stomach Chinese company (see my Out of the squalor and into the light: When the Shanghai wall came down).

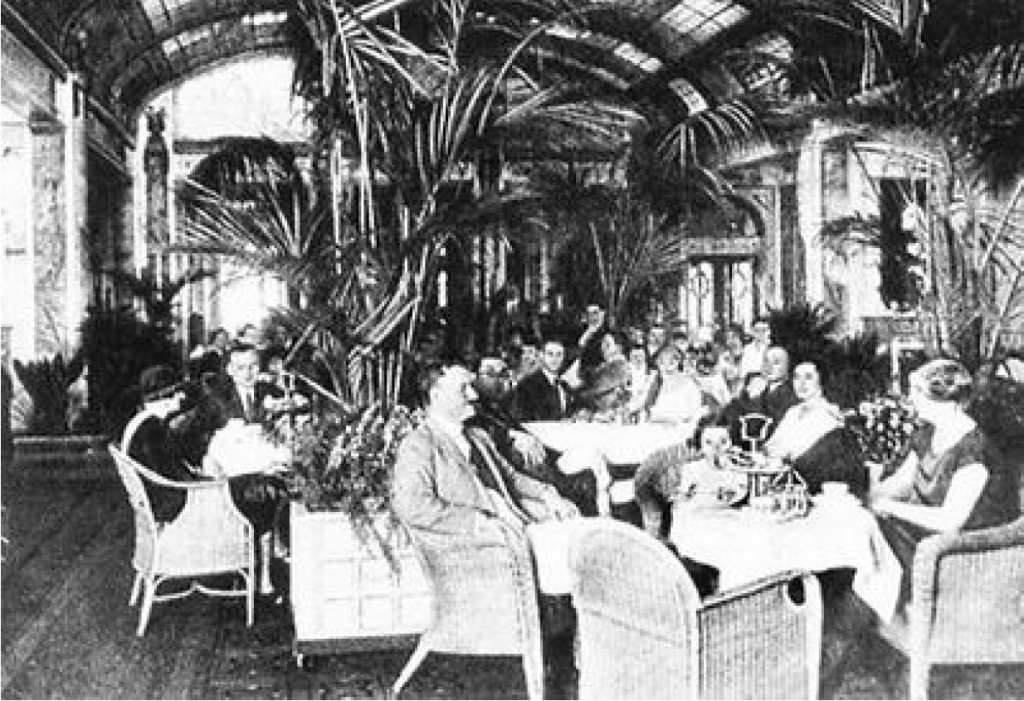

But the hotel lobby cafés in the finest international hotels in China today can scarcely compete with the grandeur of the old Shanghai hotel cafés. (The date of the photo at left is unknown but the dress styles suggest the 1920s.) These lobby venues formed in turn the model for the many independent cafés that soon sprang up in the concessions, boasting equally grandiose Victorian decor, vast atriums, spiral staircases, floor-to-ceiling windows, and towering potted plants. The line between ostentatious café, nightclub, and ballroom was a thin one. Any café worthy of the name required the full panoply of food and alcohol, a dance floor, and a state-of-the-art gramophone horn if not a live band. In an age without air conditioning, afternoons in enclosed places in Shanghai’s heat could be insufferable; most flocked to the cafés only in the evenings once the temperature had cooled and stayed until the early hours of the morning (Chen, Study). As the twenties got seriously underway, young Chinese women started showing up, feet no longer bound and eager to dance. They also started appreciating coffee.

Smaller cafés as well began appearing to cater to more contemplative types. Early Chinese enthusiasts came up with the metaphor to “incubate” (孵 or “hatch”) in the more subdued type of café with coffee and a book (Zhou). Shanghainese novelist and café aficionado Zhang Ailing (1920-95), known abroad as Eileen Chang, captured the tail-end of the era with nicely ironic portraits of the more intimate, bohemian coffeehouses and bakery cafés of the early 1940s. In her essay “Seeing with the Streets” (from Written on Water) she writes:

The Western-style coffee shop next door is filled with the clamor of machinery each night, lights blazing, turning out pastries and sweets. The smell of eggs and vanilla extract lingers until dawn before dissipating into the air. In a big city where “bills keep falling from the sky even when you’re inside,” it seems almost unreasonable that the owners allow us to enjoy the aroma without having to pay a cent. But the aroma of the cakes made by our sweet-smelling neighbor far outstrips their flavor, a fact that becomes apparent as soon as you’ve eaten one. Perhaps everything under heaven is the same: a cake that’s done isn’t as good as a cake in the process of being made. The glory of a cake is in the aroma it gives off as it bakes. Those who enjoy life lessons may well find one here.

The olfactory details are telling. They used vanilla in their baked goods, an ingredient that dropped out of Chinese baking in the decades that followed and only being reintroduced today. The venue was brightly lit but seemingly for the bakers’ not customers’ benefit. If the kitchen was not wholly demarcated from the seating area, few seemed to mind. But the quality of their cakes was questionable. In Chang’s novella Lust, Caution, set in the same years, the heroine Chia-chih arranges a furtive assignation with the politically powerful lover Mr. Yee by visiting two cafés in succession as she is directed via phone calls where and when to be picked up in his limousine. The cafés are deliberately unassuming and discreet. She hasn’t much to say about the first, apart from just enough details to help us visualize its interior:

As it was only midafternoon, the café was almost deserted. Its large interior was lit by wall lamps with pleated apricot silk shades, its floor populated by small round tables covered in cloths of fine white linen jacquard—an old-fashioned, middlebrow kind of establishment.

The second, “small café” near Jing’an Temple in the International Settlement, is no less informative for being atypical and something of a dive:

Most of the café’s business must have been in takeout; there were hardly any places to sit down inside. Toward the back of its dingy interior was a refrigerated cabinet filled with various Western-style cakes. A glaringly bright lamp in the passageway behind exposed the rough, uneven surface of the brown paint covering the lower half of the walls. A white military-style uniform hung to one side of a small fridge; above, nearer the ceiling, hung a row of long, lined gowns—like a rail in a secondhand clothing store—worn by the establishment’s Chinese servants and waiters. He had told her that the place had been opened by a Chinese who had started out working in Tientsin’s oldest, most famous Western eatery, the Kiessling….She waited, the cup of coffee in front of her steadily losing heat.

The Kiessling (凯司令) is the only coffee restaurant of old Shanghai that survives today in its original location, at 1001 Nanjing West Road. Of course, the former Cathay Hotel lobby café and bar, mecca of the 1930s Shanghai foreign elite, now the Peace Hotel, also remains in operation, but again that’s not an independent coffee business.

The Kiessling was one of the few “bourgeois” establishments allowed to remain open during the Cultural Revolution. Shanghai writer Cheng Naishan (1946-2013), reminiscing on this time in an essay on coffee in her memoir Shanghai Taste, possibly refers to the second-floor restaurant when she notes a few more details such as the “distinctive German country style, with bronze chandeliers, a black oak fireplace, and lamps with georgette lampshades.” The first-floor bakery described by Eileen Chang survives but no longer has seating. Thus in Ang Lee’s 2007 film of Lust, Caution, actress Tang Wei, playing the heroine Chia-chih, sits in a Shanghai Film Studio reimagining of the Kiessling, with appropriate noir atmosphere (“Production notes”). The original Kiessling indeed opened in 1901 in Tianjin (Tientsin) by a German chef. The Tianjin shop continues to operate also as a bakery and restaurant. I first visited the Tianjin Kiessling in the early 2000s, when there were few other western cuisine offerings in the city. The interior was unchanged since its beginnings or at least looked authentic enough. Returning to the restaurant a decade later, I found the food unpalatable, but their dalieba, those big round loaves of Russian-style sourdough bread with nuts and dried fruit, in their first-floor bakery, was hearty and scrumptious.

Several other Shanghai coffee establishments with some connection to the glory days survive, if in name only. Deda (德大) Western Restaurant goes back to 1897, when it began as a butchery on 177 Tanggu Road in the Hongkou area, where the Japanese and Russian Jewish communities—both serious café cultures—intermingled. It moved to nearby Sichuan North Road after the war in 1946 and was nationalized in 1949. It remained open, now with a separate café section, but moved again in 1986 to 473 Nanjing West Road, where it continues to operate as a restaurant and café. A second branch opened in 2009 on 2 Yunnan South Road, also near People’s Square (the old Race Course in the British Concession). Gongfei Café (公啡咖啡) opened in 1929 also on Sichuan North Road and became a favorite haunt of intellectuals and revolutionaries such as Mao Dun and Lu Xun. The café closed during the war and the building was razed in 1995. It reopened in 2020 under the same name at nearby 251 Duolun Road. Its new incarnation is a sleek modern café with old-Shanghai accents and an attached bookstore. Mars Coffee Shop opened in 1941 at 147-149 Nanjing East Road. It was renamed Donghai (东海) Restaurant in 1954 and Donghai Coffee Shop in 1988, finally closing its doors in 2007. It reopened in 2019 at a new location (110 Dianchi Road) and has been beautifully furnished in the old style, replete with a big decorative gramophone horn.

One of the many cafés opened by Russians was Kavkaz (卡夫卡斯) on Huaihai Middle Road in the French Concession. We have a surviving photo of the exterior and one that purports to be of the interior, though the windows don’t seem to match up (“Cafe situation”). It’s still a good example of the common “train car” design of many former Shanghai cafés, with a row of window-lined high-backed booths a la the American diner. This proved attractive to young couples who could interact with a veneer of privacy, especially so for Chinese women who for the first time were venturing out of the house. A still from the film Cityscape (Dushi Fengguang, dir. Yuan Muzhi, 1935) shows a typical café booth; the camera zooms in through the streetside window and opens into a busy interior (Jia). High-backed booths became the norm in China right up until our time and had a similar purpose. I recall shabby “coffee” bars in Beijing in the late nineties with high-backed booths. The heating was seemingly turned down to give couples an excuse to drape themselves in their long green army-style coats for a little privacy. A movie theater in Beijing’s Xidan District, long since demolished, had deep love seats for couples to cocoon themselves in. A smaller theater in the basement was unlit and you were guided there by flashlight. No one was there to watch the generic Hong Kong action flicks, nor were they as particular about draping themselves (hotels in those years forbade unmarried couples).

Also in the late nineties, the capital experienced a teahouse boom; only a handful had existed in the prior decades, in contrast to southern China where teahouses had always been more plentiful. A popular chain whose name escapes me popped up around the city, open 24 hours with private tatami-lined rooms, ostensibly for “business” dealings that took until morning; the chain folded only a few years later. Also at this time, UCC (上岛咖啡), the first homegrown, nationwide café chain opened throughout the country, along with many imitators. They all had similar dark interiors and high-backed booths, thick with cigarette smoke, businessmen shouting into their cellphones or plying their secretaries with drink. Many were located on the second floor of buildings for added privacy from the street. In addition to various grades of whisky and “XO,” the Chinese term for cognac, acceptable siphon-brewed coffee was on the menu for the first time, with varieties of bean (not always fresh) including Hawaiian Kona and Jamaican Blue Mountain. As Chen Danyan writes of this breed of café in Shanghai, “If a single woman placed a pack of cigarettes on the table, it was often an indication that she was a prostitute. If middle-aged men and women came together, their behavior was always chaotic, often suggesting adultery” (Romance). These old-school booze cafés have largely gone by the wayside, though you can still find them in backwater cities.

I emphasize “for the first time,” since the art of coffee making had been altogether lost until then. The half century between the last cafés of the post-war years and the return of the bean was a Gobi Desert of cheap powdered coffee.

By the time the Communists triumphed, café culture had spread to all the coastal cities, even during the terrible years of the Japanese invasion and occupation (1937-45) and subsequent civil war (1946-49). Shanghai was attacked in August and Nanjing devastated in November of 1937; Shanghai’s International Settlement fell to Japan in 1941, the French Concession in 1943. During all this time, café life never ceased. We must not be under the illusion that café culture was confined to Shanghai. The novelist Lao She (Rickshaw Boy), temporarily living in wartime Wuhan in the spring of 1938, just before the Japanese assault on that city, made this nostalgic yet ambivalent observation about the younger generation’s carefree ways in Qingdao, where he had been teaching and which had succumbed to Japanese occupation the previous January. Despite that, café life there too carried on, as it must:

Is it really appropriate for Shandong University to be located in Qingdao? Dance halls, cafés, cinemas, bathhouses… Can one concentrate on studying amidst such a vibrant world?… Someone who hasn’t been to Shandong University might easily imagine that Qingdao, being a place with a cosmopolitan atmosphere, must also have Shandong University students dressed in Western clothes, like children of overseas Chinese. That is simply not the case.

Lao provides more inadvertently colorful details about café-goers in Hankou, the site of Wuhan’s former foreign concessions:

If—oh, I dare not even think of it!—she’s that hypocritical, pretentious woman who learned her ways from movies, and she insists on coming with me, even while fleeing, wearing high heels. What will I do? I’ve seen with my own eyes, in the most luxurious restaurants and cafés of Hankou, women putting on a show for their husbands. They’re supposedly very fond of the arts. Whether their husbands are artists, I don’t know; I just worry that if their husbands are indeed writers, will they have time to write besides serving their wives? If he has to write after returning home from the café late at night, can she bear to see his miserable face at dawn—a demeanor and posture completely opposite to that of a male star? (A Delightful Loneliness)

Almost everything we know today about the art of coffee making had been perfected in Europe over the course of the nineteenth century. For instance, according to William H. Ukers’ encyclopedic tome All About Coffee, published in 1922, coffee artisans and scientists were unanimous, then as now, that a drip maker with a paper filter produced the best coffee, though paper contained chemical residues and some preferred cloth or muslin. Boiling water should be cooled to 195-205 F (90-95 C) before contact with coffee, and beans should be stored airtight and ground only before use. Colombian, Indonesian Java and Mandheling, and Brazilian Bourbon Santos were favorites, and precise blends were recommended. Electric percolators were in widespread use but condemned by enthusiasts, as they overcooked the coffee; boiling coffee directly in a pot (“cowboy coffee”) was also common and likewise viewed with derision.

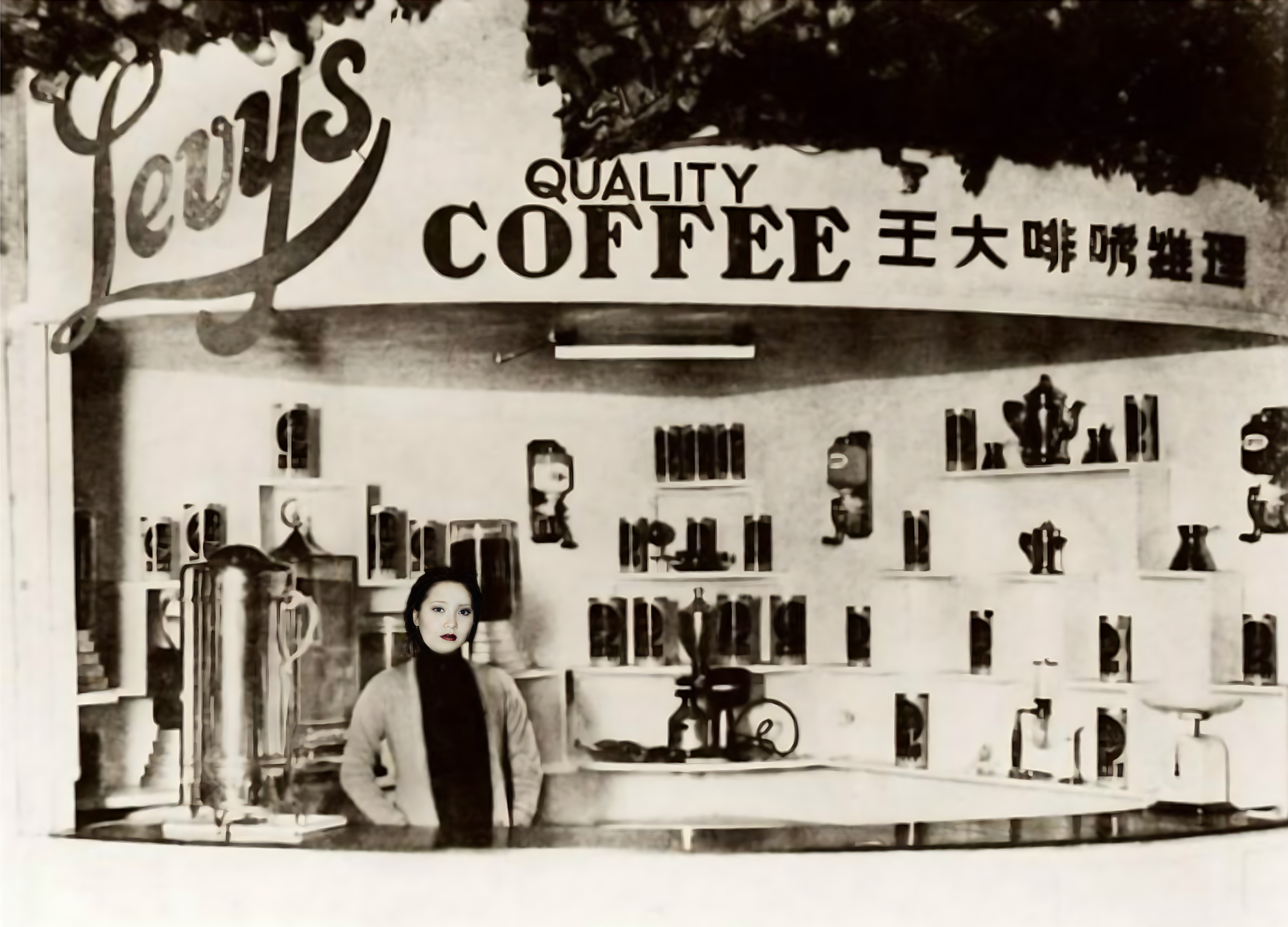

This coffee knowledge was imported and fully absorbed in tandem with café culture in China by the early decades of the twentieth century. An extremely valuable photo survives, for what it reveals about how coffee was served in the 1930s, of Levy’s “Quality Coffee” Café in Shanghai. A relatively clear but cropped version appears in a Sixth Tone article and credits the Shanghai Library as its source (Huang). I was not able to get my hands on the original, but there is a grainier, uncropped version circulating online, pictured below (sharpened with AI tools). It shows a female attendant standing behind a counter selling coffee and coffee equipment. On the wall surrounding wall-mounted hand grinders are cans of coffee, perhaps ground but surely whole beans as well, since in the center sits an electric coffee grinder that appears unplugged and therefore also for sale. To the right are traditional coffee pots and what look to be several Turkish cezves or ibriks. On the bottom shelf between two coffee cans is a Japanese Hario brand siphon coffee maker, whose design is unchanged till this day. Japanese siphons make superb coffee and I’ve used them for years.

Behind the lady, at left, we see two large coffee urns of the sort used in restaurants and cafés, either for dispensing coffee or brewing it by drip, percolator or steam. A similar urn to the one in front is also visible at back in the Cityscape film still. Again consulting Ukers, there were four types of urn for making coffee: the Napier steam coffee machine (a double urn, one for producing steam pumped to the other by pipe), the King Percolator (not a pumping percolator but a paper filter drip), an upward-infusion machine similar to the Italian Moka coffee maker (invented in 1938), and a pumping percolator. The pumping percolator urn may have produced a superior brew to the smaller home-use varieties: “After the ground coffee has infused for about six minutes, a screw device raises the metal sieve, the pressure forcing the liquid through the cloth sack containing the ground coffee” (Ukers). Curiously, the square-shaped urn behind her is mounted with Turkey’s star-and-crescent symbol at top. Unless there’s a coffee historian around who can enlighten us, the two urns in the picture remained unidentified.

And then, as evanescent as arabesques of vapor from a hot cup of coffee, it all vanished after 1949, as if never having existed. Indeed it never had for the vast majority of Chinese, who had scarcely ever heard of coffee, much less had access to it. A few state-run cafés held on tenaciously in Shanghai for a shrinking elite of coffee addicts (Cheng). During the Cultural Revolution, only those with foreign exchange certificates could buy coffee beans from “Friendship Stores” that had been set up for the benefit of the foreigners remaining in the country. Tins of Shanghai Brand ground coffee premixed with sugar became gift items (“Shanghai’s original”). Coffee drinking was increasingly disapproved of, forcing it underground. Those with cash to spare put “ground coffee in a bag, added it to a pot of milk and boiled—just as fragrant and rich. Since coffee cups had been confiscated, we poured it into our rice bowls to drink.” Those without cash to spare—just about everyone else—found sad substitutes such as roasted barley (Cheng). Personally, if coffee ever disappears, the best substitute would be quality Pu’er tea from Yunnan Province, China’s coffee-growing region, mimics coffee’s body, richness, and color, with a special taste all its own.

“Thirty years later,” as Chen Danyan also writes from firsthand experience, “the new generation of modern people didn’t really know how to drink coffee. They didn’t know to take the small spoon out of the cup and put it on the saucer before drinking. The new coffee shop owners didn’t really know how to brew coffee either, always using Nestlé instant coffee to appease customers” (Shanghai Salad). Reminiscent of my hunt for something as odd as a coffeehouse on a trip to Urumqi in Xinjiang Province in 1995. The Uyghurs were after all ethnically Turkic and I had naively thought coffee might be ingrained in their DNA. They drank tea exclusively. I did stumble upon something resembling a café, with coffee actually on the menu. After some digging around, the waitress presented me with a stainless-steel mixing bowl half filled with lukewarm water, a ladle, and an unopened jar of Nescafé, hoping I could figure it out.

We were in the bleak Nescafé era. In Beijing at the time, a state-run store across from the Friendship Hotel where I lived sold gift boxes with a transparent front revealing a Nescafé jar, a jar of powdered creamer, a pair of gold-rimmed Vienna-style coffee cups, and imitation gold-plated spoons. Large cans of ground Maxwell House coffee were available at the Friendship Store. I scrounged up a plastic coffee dripper and paper filters somewhere for daily use. Rewind a few years to my first trip to China in 1990. I was living in Japan at the time and traveling with a Japanese male friend. Coffee is just as important to the Japanese as it is to us, even more so. Our town in rural Wakayama was jeweled with elegant coffeehouses known as kissaten serving hand-brewed siphon coffee. The local liquor shop roasted their own coffee beans and hand-poured their coffee for patrons. My friend brought along for emergency purposes a device of the sort only the Japanese can cook up—a pressurized can that squirted concentrated liquid coffee into a cup and you added hot water. In Chengdu in Sichuan Province, a week after our arrival in Shanghai, on the north bank of the Nanhe River not far from our hotel, we found a café. I had the presence of mind to snap a picture of my companion and our cups of instant coffee. Today, the strip of little cafés and restaurants is gone and has been turned into a park.

In Shanghai I did not have the presence of mind to snap a photo of the one coffee establishment we visited. Our guide said it was famous for its steamed coffee. We found seating in the second-floor gallery area which looked down upon the first floor. It was very crowded and brightly lit. A waitress brought our coffee in a metal pot, generously mixed and steamed with milk and sugar; no option for black coffee. Contemporary Shanghainese Chen Danyan claims that Blue Mountain coffee, Mocha, Irish coffee, Japanese iced coffee, Italian cappuccino, and American regular coffee were already on offer, along with homemade cheesecakes and muffins, in Shanghai cafés at this time (Shanghai Salad). This café may have been the same venue, the Times Café (时代咖啡馆), which she photographed in 1992 for her compilation of Shanghai history, Romance and Leisure in Shanghai. It also had a surrounding upper-floor gallery but it seems larger in the photo than the place we visited. The Times Café has long since closed and I will never know.

Hunkered down in Beijing for years, I didn’t make it back to Shanghai until 2008. Good coffee was easy to find by then, and I started taking frequent trips to the city, where a revolving cast of Chinese and foreign friends were also passing through. Someone introduced me to Niny Lam (at left in the photo), who had opened the lovely Santa Cecilia Music Café (茜茜莉亞) in the former French Concession. I first visited Santa Cecilia in 2012. Niny had played the violin professionally in Europe for years before returning to China, and her valuable collection of violins was displayed on the second floor of the café. Her husband was a cellist and professor of music at the nearby Shanghai Conservatory of Music. The café in this cultured neighborhood conjured up French Concession-era Shanghai and the coffee was satisfying. I gave them CDs of Gabriel Fauré piano music to put on the stereo. But customer traffic wasn’t enough to assuage Niny’s worries about staying afloat. The location could not have been more ideal—across the street from the planned Shanghai Symphony Hall. She wasn’t sure she’d be able to hold out until 2014 when the concert hall was slated to open. Santa Cecelia didn’t make it and soon closed its doors. It was unfortunately ahead of its time and a bit too sophisticated for prevailing tastes.

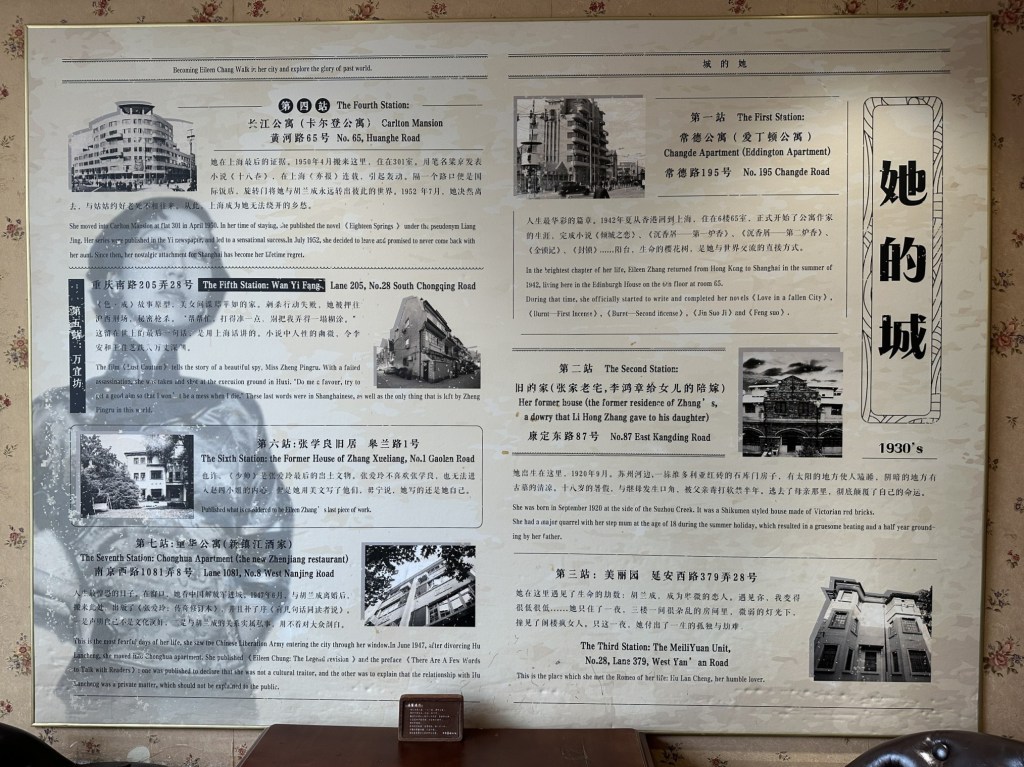

This would soon change. In 2008 an interesting café opened in the Changde Apartment Building just off Nanjing West Road near Jing’an Temple, the same area in the International Settlement that had been previously populated by cafés in the 1930s and 40s, and the building where Eileen Chang, the Lust, Caution author discussed above, lived from 1939-47. She was a frequent visitor of a café occupying the same ground-floor space as the current Qiancai or “Thousand Color” Bookstore café (千彩书坊), which is devoted to her. The café is so popular that you have to first purchase a beverage before being allowed to choose a seat, and Americano is priced high at 50 yuan ($7). To give you an idea of how revered Chang is China, the owner of Ourtopia (托比亚), a bookstore café I recently visited in Dali, Yunnan Province, mounted her pick of the 100 most famous international authors on a wall, with photographs and brief descriptions of each. Only one was Chinese: Eileen Chang. In the Qiancai Bookstore, literary books, including everything by and about Chang line the walls, and a back wall contains an introductory poster. The proprietress (behind the counter) uncannily resembles the author. I visit the café whenever I’m in the city.

The closest thing to a beverage salon for intellectuals in 1990s Beijing was the Sanwei Shuwu teahouse (三味书屋), whose story I tell in Insights into China, Part 5: An invitation to a party. There were no coffeehouses in the city until an American opened one on the Third Ring Road at Sanyuanqiao around 1996, replete with checkerboard flooring and arabica-grade coffee (Well, there were coffee bars with names like “Jane’s Café” and “Melody’s Café,” the predecessors of the UCC-style booze cafés and whose raison d’être was prostitution.) It folded after a year or two, but the owner might have been the same entrepreneur who launched a whole-bean brand called Arabica around the same time, which did last but you had to know which stores sold it. In 1998 Starbucks launched its first shop nationwide across from the east gate of People’s University, with Ming Dynasty-style hardwood furniture. It was crowded with young people and I was a frequent visitor. Other Starbucks soon flourished like mushrooms. Some shops, like the one at the Lido Hotel, were notorious prostitute pickup spots. But the chain performed a needed service in alerting local café owners to get up to speed on coffee quality.

At the turn of the century, the idyllic string of interconnected little lakes in the Shichahai neighborhood in central Beijing finally had its eureka moment (I had been wondering when it would come) and exploded with bars and cafés. The first one to open, in a former vine-covered house overlooking Qianhai (the “Front Lake”), was too understated to bother even with a sign. They were eventually persuaded to adopt a name and styled themselves the “No Name Café” (无名咖啡). It quickly became a hit not only for being one of the first of its kind, but the foreign customers could get away with smoking pot since the super-laid-back staff pretended not to know what it was. It’s long since been razed. Also in 1998, the first local coffeehouse chain proper, with acceptably brewed Illy coffee and just the right cerebral ambience, opened in a strip of old lanes squeezed between Beijing and Qinghua Universities, a tad snobbishly entitled “Sculpting in Time” (雕刻时光) after a book of the same name by filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. It moved to the Beijing Institute of Technology when the lanes were demolished in 2001. That shop was still going strong on my last visit. Over the next decade Sculpting in Time opened shops throughout Beijing and other cities. They got certain things right from the start, enabling the chain to thrive for over two decades: comfortable wooden furniture and warm, earth-toned color schemes. But then something unexpected happened in the city in the early 2010s: the coffee palace invasion from Korea.

Beijing has long catered to grandiose gastronomic establishments, whereas Shanghai has always been more intimate and European; Beijing has the best craft brewpubs in China, Shanghai the best wine bars. But this was unprecedented. Sparked by South Korea’s Caffe Bene (咖啡陪你) chain, Beijing in the teens witnessed an eruption of massive cafés with a very particular design: endless interiors sometimes layered on several floors, roughhewn and rustic woodwork, intentionally mismatched furniture, and chandeliers galore—resembling furniture or lighting emporiums more than coffeehouses. In my Beijing neighborhood of Shuangjing alone sprouted five such coffee palaces, one of which, Joy Life, was simply the most dazzling café I had ever seen, if outlandishly so, with three formidable floors of bizarrely imaginative furnishings and so much seating they could never fill the space. These coffee palaces, and their elaborate waffle creations that enticed locals more than boring Frappuccinos, quickly rendered Starbucks and Costa Coffee passé, though the western chains managed to hang on and weather the storm. Just as suddenly, the Korean wave receded and the coffee palaces vanished. Predictably, the rents were unsustainable without the clientele constantly at capacity. Like the American book superstores Borders and Barnes & Noble, they were too good to be true and collapsed under their own weight. The most successful chain, Maan Coffee (漫咖啡), which had unveiled stores throughout Beijing and other cities, still has a handful of shops. Starbucks survives as well, though only by expanding into second- and third-tier cities. Its recent domestic competitor, Luckin Coffee (瑞辛咖啡), has nailed the formula and serves pretty much the same quality drinks at lower prices and more convenient pickup and delivery service using its cashless app.

For every café in China that fails or gets the boot by fickle landlords, two new ones open up. The latest trend has pulled back from the wasteful extravagance of the mid-’10s to adopt a clean, minimalist look, the color white predominating. The Voyage Coffee chain exemplifies this with its expansive store (since closed) in Beijing’s revitalized west Qianmen and several other shops in Shichahai and the 798 Art District and in Shanghai. Another quality chain, Soloist Coffee (独奏咖啡), has adopted curious furniture items (old streetcar seats, framed antique maps) and repurposed the interiors of old buildings. What has made this phase more than a mere shift in fashion is the improved coffee experience, now that the younger generation of Chinese baristas have caught up with the rest of the world, and sourced beans and hand-dripped brew are becoming the norm. Then in 2020 Covid washed away many businesses in its wake. When it receded three years later, the cafés that made it did so primarily because they had a solid customer base rather than antiseptic decor or creatively awkward furniture. Try to find a seat on weekends in The Place (世贸天阶) branch of the Jamaica Blue Coffee Shop chain in Beijing. It’s an intimate, understated café, and the coffee and edibles are reliably top-notch. But it’s the customers that form the decor.

What many recent cafés seem to have collectively grasped is that distinctiveness rather than fashion and copycatting provides a winning formula. And this has, paradoxically, brought about another fashion, the weird phenomenon of (in the current slang) “Internet celebrity little sisters” (网红小姐姐), “surveying,” “scoping out” (探店, 种草), and “punching in” (打卡) at select cafés, where they spend hours posing in seductive clothes and snapping photos of each other, using the venue’s unique or stunning setting as a backdrop. Most seem to do this just for fun but many others, evidently unemployed, treat this as serious business, a job in its own right. If an attractive female gains 3,000 to 4,000 followers on Rednote or Douyin (Chinese TikTok), she can create a “shopping cart” for selling products; 100,000 followers and she becomes a de facto influencer who can pull serious money. Cafés owners generally encourage their presence as a free form of advertising for the establishment, even if the “little sisters” order the cheapest drinks or try to get away with ordering nothing.

To others, the little sisters can be a nuisance. They occupy the venue’s restroom to change into several sets of clothes. To get the right angle, they accidentally back up into you and will even ask you to shift or move seats. As one server confided to me, they can “make a lot of noise, disturb other customers, misuse their flash and fill lighting, bring a lot of stuff and leave it everywhere, making a mess of the place, and engage in some indecent posing in extremely revealing clothes.” These fashionistas aren’t, of course, confined to China; it seems to be a global trend in the Instagram age. I witnessed in it on a recent trip to Hanoi and Da Nang in Vietnam, whose equally awesome cafés draw the same little sisters dressed in the same frilly outfits as in China. A division seems to be opening up: cafés that are expressly designed to attract influencers, and cafés that are expressly designed to discourage them—workspace cafés with long tables for laptop users. They were quite numerous in Vietnam, less so in China, where the concept is still new. Unlike the rest of Southeast Asia, China’s visa and internet restrictions don’t fly with digital nomads. But China now has an infinite variety of coffee establishments and enough of its own netizens who seek out the quieter variety of café. It’s comparable to the situation a century ago when Shanghai cafés had to decide whether to be cabarets or cozy incubators.

Another way to look at this distinction is between cafés as havens or sanctuaries and cafés as arenas or theaters: one wanders to the former and within the latter. The notion that people could step off the productivity treadmill to tramp randomly through a city’s streets for no other purpose than making unexpected discoveries along the way was popularized by late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Parisian poets, surrealists, and (later) the situationists, a history I trace in From Van Gogh to the Camino de Santiago: Symbolic travel and the modern pilgrim. This concept of “wandering bohemians” (流浪的波西米亚人 or 闲逛者) was picked up quickly by Chinese writers and artists in 1930s Shanghai. Many Chinese in that era had lived or studied in Paris—the painters Xu Beihong and Pan Yuliang and the writer Qian Zhongshu come to mind—and had their eyes opened by European Modernism; it was also at this time that China was flooded with the first wave of western literature in translation (Li). Locals were not merely leaving the teahouses to venture warily into the concessions’ cafés; they “sought the thrill of wandering among no fixed routes…discovering many urban secrets that ordinary people cannot…lingering in inconspicuous corners of cafés” (Zhou). Other Shanghai cafés, by contrast, were more interactive. They drew the ordinary of both sexes for a stricter purpose—dancing and coupling. These were cafés as arenas for performing rather than dreaming and incubating in.

Cafés today, however, are not for dancing; there are bars and clubs for that purpose. But the grander and more scenic of establishments are transformed into a theater of sorts, a dramatic space, when swamped upon by the Internet celebrity little sisters. Whether or not they are paying any attention to you, you are nevertheless their audience; even as they pretend to be minding their own business, they are highly conscious of the impression they are making on the customers around them. Despite the final product being intended only for the cellphone, they are very much performing their product on stage in the flesh. Their seeming disregard for their audience is nothing other than the classic theater’s invisible “fourth wall” behind which the players perform oblivious of the audience sitting before them. This makes more sense if you understand public interaction rituals in China. When people get into an argument outside, say a traffic scrape, they strut and threaten each other oblivious of the crowd forming around them even as they exaggerate their antics precisely for the benefit of the crowd. Quarreling couples will similarly stand back-to-back right out on the street in proudly defiant poses, something other cultures might find embarrassing and purely a matter of privacy (see my The many faces of Chinese face).

I’ve always been partial to the larger sort of cafés, and I have always wondered what it is about space that feels so luxurious. Is it the suggestion of wealth, of living or lounging for a few hours in a grand interior as if it were one’s own? Restaurants and bars don’t seem to rely as much on the same appeal (though it can hardly hurt); in them you’re more caught up in a process—the potent fragrances of the food and drink, the company and the conversation at hand, the contracting funnel of inebriation—than in a place. You’re in, and you’re out. In a café, on the other hand, there is no hurry to get up and leave, whether due to pressure to vacate your table, or because you’ve had enough to drink, or you’ve succeeded in scoring a one-night stand. You are able, indeed encouraged, to stay as long as you want. In the café, time settles and slows down. You’re left to your own devices and resources. You’re invited to take in the surroundings, merge with them as it were. And the surroundings, therefore, are all the more important.

FOOTNOTES

- Data on number of coffee and tea establishments are drawn from multiple sources on the web. Figures can vary, as the terms “café,” “coffeehouse,” and “coffee shop” may be lumped together or not depending on the source. Traditionally, a café is a place for drinking coffee but which may offer alcohol and a modest range of dishes, comparable to the French bistro; it may also refer to a full-blown, even upscale restaurant, a bar, or a cabaret. A coffeehouse or coffee shop, by contrast, more exclusively designates a place for drinking coffee and is associated with the northern European and Anglo-American countries. “Coffee shop” in American usage can alternatively designate not a coffeehouse but a small restaurant or diner. Chinese generally employs the term kafeiguan (where kafei is a phonetic rendering of both “café” and “coffee”) to refer to any independent coffee establishment. In this essay I employ the terms café and coffeehouse interchangeably. As for the snobbish accent in the spelling of “café,” as opposed to “cafe,” linguistically speaking it indicates that we still retain the French pronunciation; that is, it doesn’t rhyme with “safe,” as it will in the future if the word becomes fully anglicized. But practically speaking, when doing research, a search of references to “cafés” turns up far more results than “cafes.” Café with the accent is thus still recognized as the dominant spelling. ↩︎

- For a deeper dive into 1920s-40s Shanghai coffee and café culture see Chen, Study; Hu; Huang; Jia; Li; “Shanghai’s original”; Shi, “China’s bean town” and “Brief history”; Yong; Zhou, in References below. ↩︎

REFERENCES

“Cafe situation in the Concession era.” Shanghai and China Architectural Guide and Development Observations CAMSA Architectural Glass Room (Blog), 22 Jan. 2021 [http://blog.livedoor.jp/camsa/archives/5725874.html].

Chang, Eileen. Lust, Caution: The Story. Trans. Julia Lovell (Anchor, 2008).

Chang, Eileen. Written on Water. Trans. Andrew F. Jones (NYRB Classics, 2023).

Chen, Danyan [陈丹燕]. Romance and Leisure in Shanghai [上海的风花雪月] (from Shanghai Trilogy [上海三部曲]) (Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House, 2020).

Chen, Danyan [陈丹燕]. Shanghai Salad [上海色拉]. (Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House, 2012).

Chen, Wenwen [陈文文]. A Study of Shanghai Coffee Shops in the 1920s-1940s [1920-1940年代上海咖啡馆研究]. M.A. Thesis, Shanghai Normal University, 2010.

Cheng, Naishan [程乃珊]. Shanghai Taste [上海 Taste]. Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House, 2008.

Hu, Yuehan [胡悦晗]. “Teahouses, restaurants, and coffee shops: The leisure life of Shanghai’s intellectual community during the Republican Era (1927-1937)” [茶社、酒楼与咖啡馆:民国时期上海知识群体的休闲生活 (1927-1937)], Journal of Hengyang Normal University, 36(2), 2015.

Huang, Wei. “How Shanghai’s coffee culture brewed up a revolution,” Sixth Tone, 16 Mar. 2022 [https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1009898].

Jia, Yihua [贾艺华]. “The imagination of cafés in early Shanghai films from the perspective of media geography” [媒介地理学视阈下早期上海电影中咖啡馆想象], Shanghai Vision [上海视觉], 2025(0/2): 146-154.

Lao, She [老舍]. A Delightful Loneliness: Lao She’s Essays [可喜的寂寞:老舍散文]. Ed. Fu Guangming (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Literature & Art Publishing House, 2014).

Li, Yongdong [李永东]. Concession Culture and 1930s Literature [租界文化与三十年代文学]. Ph.D. Dissertation, Shandong University, 2005.

Ou, Dongqu, Wu, Si, & Ni, Yuanshi [欧东衢, 吴思, & 倪远诗]. “Guiyang: A hub for coffee shops, density exceeds Shanghai [贵阳:众“咖”云集,咖啡馆密度超上海], Xinhua Daily Telegraph [新华每日电讯], 23 Jun. 2025.

“Production notes – Lust, Caution.” Focus Features, 19 Jan. 2010 [https://www.focusfeatures.com/article/production_notes___lust__caution].

“Shanghai’s original coffee brand: The bitter-sweet history of C.P.C. Coffee,” M.O.F.B.A. Blog, 5 May 2021 [https://www.mofba.org/2021/05/05/shanghai-s-original-coffee-brand-the-bitter-sweet-history-of-c-p-c-coffee/].

Shi, Mengjie [石梦洁]. “A brief history of coffee drinking in Shanghai” [魔都喝咖啡简史]. Pengpai [澎湃] (Shanghai Local Chronicles Library), 30 Nov. 2020 [https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_10199210].

Shi, Mengjie. “China’s bean town: How Shanghai brewed up a cafe craze,” Sixth Tone, 16 Feb. 2022 [https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1009658].

Ukers, William H. All About Coffee (New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company, 1922).

“What remains: Shanghai’s 100-year-old western restaurant, Deda.” Smart Shanghai, 8 Sept. 2021 [https://www.smartshanghai.com/articles/dining/the-story-of-100-year-old-cafe-restaurant-deda].

Yong, Jun [雍君]. “The past and present of Shanghai-style coffee culture” [海派咖啡文化的前世今], Shanghai Enterprise, Aug. 2021.

Yu, Zemin [余泽民]. Looking at Europe from a Café [咖啡馆里看欧洲]. Shandong Pictorial Publishing House, 2008.

Zhou, Siyu [周丝雨]. Shanghai Cafes and Literature [上海咖啡馆与文学]. M.A. Thesis, Chongqing: Southwest University, 2014.

* * *

Other posts in this series:

Insights into China (Part 1): A walk down the street

Insights into China (Part 2): A visit to a restaurant

Insights into China (Part 3): A stay in a hotel

Insights into China (Part 4): A visit to the library

Insights into China (Part 5): An invitation to a party

The classic coffeehouse: Ten essentials

Categories: China

I haven’t visited China since the summer of 2008. I had to leave early because Shanghai’s air was so polluted it made me too sick to stay. The air was yellowish and everyone I saw on the streets wore masks.

Are you planning an episode on the history of China’s air quality — at least for the last fifty years? I’ve read that it has improved dramatically since I was last there. Is that propoganda?

It has improved dramatically, but less so in smaller, non-tourist cities. Overall it’s improving due to the switch to electric cars and clean energy projects. It would be too boring a topic for me, as I’m more interested in social life on the ground.